Carbon taxes have been around for decades, imposing a levy on the emission of carbon dioxide or other greenhouse gases (GHGs) from power plants, factories, cars and various other sources, depending on the jurisdiction.

Why has this happened? How are these taxes deployed, and how does carbon taxation differ from emissions trading?

First and foremost, what do carbon taxes actually do? Apart from the obvious outcome of raising money for governments, what is the underlying environmental goal?

Carbon taxes seek to fix a long-running economic and environmental problem: burning fossil fuels releases heat-trapping gases into the atmosphere, causing environmental damage that is borne by society at large, while the real cost of doing this for the emitter has been zero. Putting a price tag on those emissions is therefore an attempt to rectify this problem, or to use the economics terminology, accounting for a ‘negative externality.’ It places the cost back at the source of the problem.

Just like putting a small price tag on single-use plastic shopping bags led to a drastic reduction in their use in many countries, carbon taxes aim to reconnect carbon emissions with their underlying environmental cost, creating a financial incentive to find lower-emissions alternatives.

Early movers

In 1990, Finland became the first country in the world to adopt a carbon tax, according to the country’s national report to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The tax at the time was set at €1.12 per tonne of CO2, and its goal was to support energy conservation and to encourage the use of renewable fuels such as biomass to replace fossil fuels.

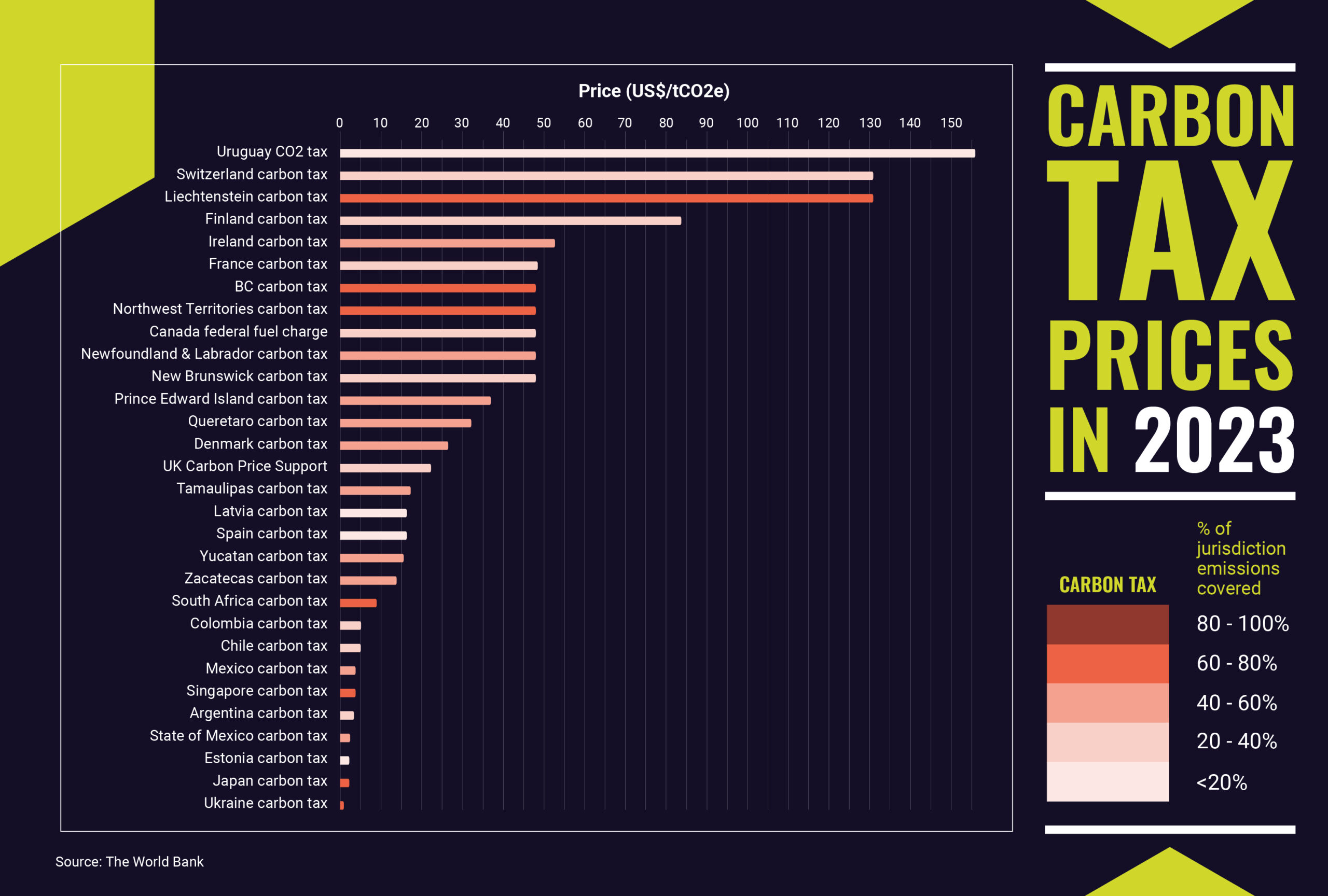

However, since then, Finland’s carbon tax has increased to $85 per tonne, according to data provider, Statista. While among the highest carbon taxes in the world, other countries with even higher carbon taxes of over $100 per tonne include Liechtenstein, Sweden and Switzerland, while Uruguay has a carbon tax of $137 per tonne as of 2022, according to Statista.

Carbon tax vs carbon trading

A key point of discussion among economists, regulators and environmental policy experts was that of carbon taxes versus carbon trading, or ‘cap-and-trade.’ While these two approaches both seek to place a price tag on carbon emissions, they do so in different ways.

Broadly speaking, carbon taxes guarantee the price that companies must pay for emitting CO2, but they do not guarantee the environmental outcome – companies could simply pay the tax and continue emitting. By contrast, carbon trading systems guarantee the environmental outcome by setting a legally binding limit on CO2 emissions, but with moveable prices determined by the balance between supply and demand.

Both systems have advantages and disadvantages. Carbon taxes offer certainty over what industry will have to pay for emitting CO2. This can be helpful when making investments that need to be profitable over a long time horizon. In particular, this certainty over cost can help when companies are seeking to borrow capital. And at an operational level, carbon taxes are generally simpler to administer than emissions trading systems.

Emissions trading, on the other hand, has a unique advantage: a company that can cut CO2 emissions at a lower cost than the price of carbon allowances can sell its surplus allowances to others. This means that, unlike carbon taxes, emissions trading is not necessarily punitive: it can generate wealth as well as simply representing a cost burden.

In this way, carbon trading systems harness market forces to drive emissions reductions at the lowest cost first, reducing the overall bill to meet the agreed emissions reduction target.

Global growth in carbon pricing

The use of carbon taxes and emissions trading systems has grown worldwide in recent years.

In 2013, the share of global GHGs covered by a carbon tax or carbon market was just 7%, according to the World Bank. By 2022, that figure had increased to 23%, according to the bank’s “State and Trends of Carbon Pricing” report released in May 2023. Combined revenues from these carbon pricing instruments came to about $95 billion in 2022, it said.

“While the uptake of emissions trading systems and carbon taxes is on the rise in emerging economies, high income countries still dominate,” the World Bank said.

“New instruments were implemented in Austria and Indonesia, as well as in subnational jurisdictions in the United States and Mexico. Australia is scheduled to recommence carbon pricing with a rate-based ETS due to start in July 2023 and countries including Chile, Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand and Turkey continue to work towards implementing direct carbon pricing,” the bank said in the report.

German carbon tax

Germany, for example, introduced a carbon tax system in 2021 to regulate CO2 emissions from sectors not included in the EU Emissions Trading System – chiefly the transport and buildings sectors. The system is similar to a carbon tax with a fixed price initially but will involve trading of allowances in future.

The system covers transport and heating fuels such as petrol, diesel, heating oil, natural gas, liquefied gas and biomass, according to Germany’s national emissions trading agency DEHSt.

Companies in these sectors must acquire CO2 certificates to cover the emissions associated with the sale of these fuels. Each carbon certificate allows the emission of 1 tonne of CO2. They started at a fixed price of €25 per tonne in 2021, and will rise gradually to €45 per tonne by 2025. From 2026, the certificates will be auctioned in a price corridor of €55 to €65 per tonne, with market demand determining the price within that range.

Consumers of the affected fuels do not participate in the system directly. Rather, the distributors of the fuels are obliged to face the costs of certificates and may pass on those costs to consumers. In this way, the carbon tax encourages end users to reduce consumption of carbon intensive fuels, for example by switching to cleaner vehicles or upgrading buildings to use cleaner fuels or cut energy wastage.

Big economies

Other large economies have opted to go for emissions trading rather than direct carbon taxation. Examples include China, which launched the world’s largest carbon market in 2021. China’s system initially involves emissions from coal and gas-fired electricity generating plants.

The United States of America, for example, has not legislated for carbon pricing at the national level, although emissions trading systems are in place in California, Washington state and several states on the eastern coast in a system called the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative.

India, meanwhile, contributes about 7% of the world’s total CO2 emissions, making it the third largest after China and the US. India has not taxed CO2 emissions directly but has imposed a tax on both imported and domestically produced coal since 2010, according to the World Economic Forum.

Putting a price tag on GHG emissions places the environmental cost of burning fossil fuels back at the source, according to the ‘polluter pays’ principle. It also sends a long-term signal to financial markets that helps companies build climate and energy transition risk into their investments. This could help promote a smoother global energy transition and help avoid more sudden and wrenching re-pricing of assets as climate impacts intensify.

Carbon pricing is clearly on the rise worldwide, made up of a mix of carbon taxes and carbon trading systems. Either way, the growth of these policy approaches indicates higher costs for emissions-intensive products and processes and creates a supportive environment for investments in cleaner alternatives.