Who buys carbon credits? What motivates organisations to buy these assets, and what does buying carbon credits ultimately achieve from the buyer’s perspective?

First and foremost, the buying and selling of carbon credits takes place mainly in the voluntary carbon market. This means organisations that buy them are not obliged to do so; rather they do this voluntarily for a variety of reasons.

In some countries, companies that emit significant quantities of carbon dioxide or other greenhouse gases (GHGs) are subject to legally binding emissions cap-and-trade systems. But not all countries have introduced such systems, and those that do exist don’t necessarily cover all sectors of the economy.

In the absence of mandatory carbon regulations, many companies recognise that their ‘social licence to operate’ depends on them demonstrating credible efforts to reduce GHG emissions to minimise their contribution to human-induced interference with the climate system.

Pressure to reduce emissions can come from multiple sources. This can include the leadership of a company, its employees, shareholders, investors or lenders.

Furthermore, civil society at large can apply pressure by drawing attention to companies that do not have a sustainability plan in place. In addition, local people in an area affected directly by a company’s emissions can play a role in pushing them toward a more sustainable business plan. Peer pressure can also come to bear on companies who see their competitors improving their reputation by demonstrating strong sustainability credentials.

Reducing emissions outside the corporate boundary

All this pressure can encourage companies to reduce their own direct emissions, or those in their wider value chain. But where direct emissions reductions are difficult, too expensive or impossible, companies have another avenue to explore when seeking to improve their sustainability: carbon offsets (also known as carbon credits).

Buying carbon credits is a way to reduce emissions outside of a company’s own operations, by investing in emissions reduction, avoidance or removal projects elsewhere, including in another country.

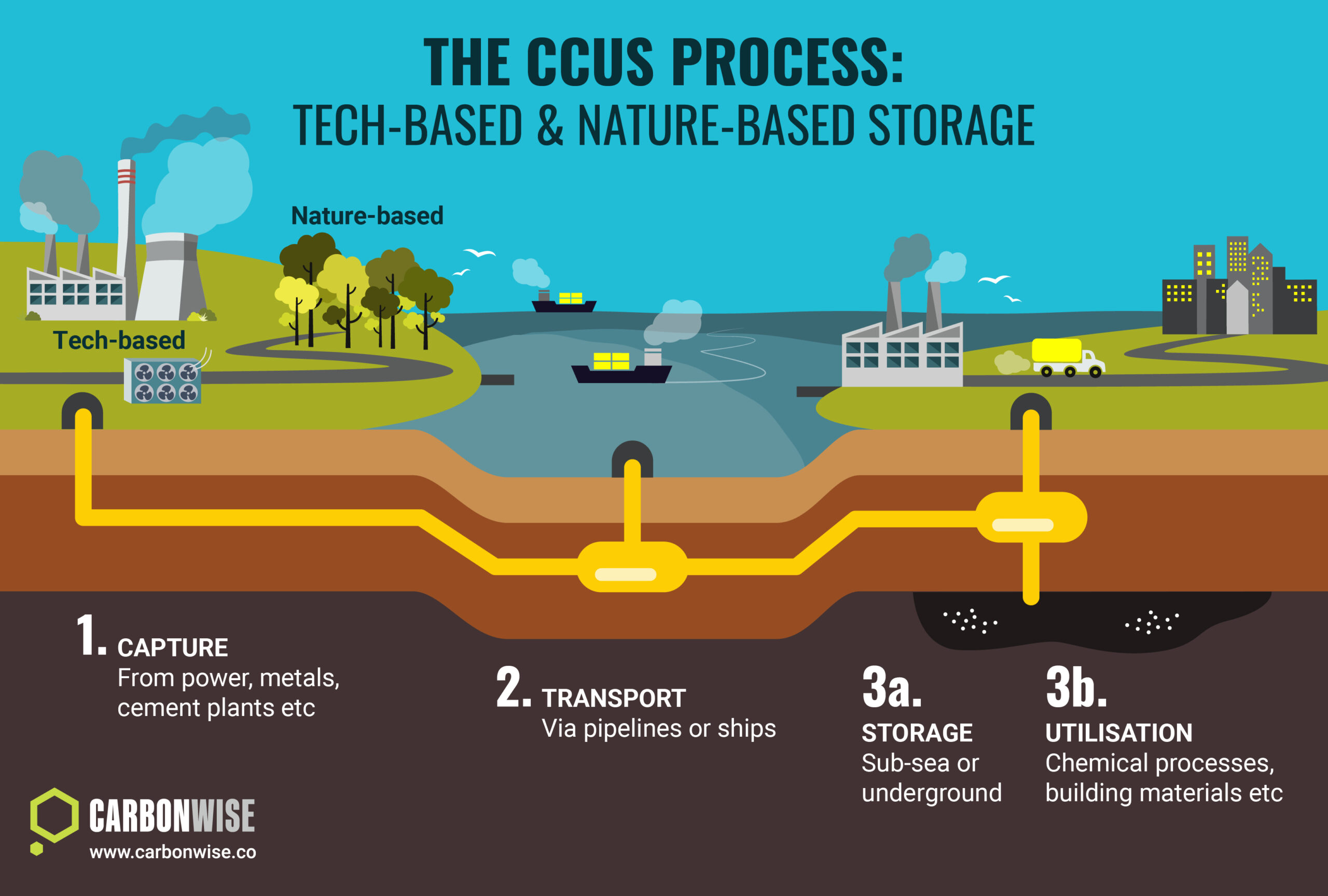

Climate projects involve the reduction, avoidance or removal of GHGs by investing in afforestation or reforestation projects, restoring degraded land or tropical mangroves, clean cookstove programs or direct air carbon capture and storage facilities, to name just a few.

Big emitters

Organisations that buy credits from these projects include large CO2-emitting companies such as energy generation or distribution companies, or those in heavy industries such as producers of metals, cement, chemicals, refineries, and transportation companies.

Other large organisations buying offsets include global high-tech information and communications companies like Microsoft and Netflix, Brazilian mining giant Vale, and global logistics and distribution company UPS.

Microsoft, for example, has committed to becoming carbon negative by 2030. This means reducing its GHG emissions by more than half, removing any remaining emissions, and then going a step further by removing from the atmosphere CO2 equal to its historical emissions by 2050, according to a company statement on CO2 removal.

Brazil’s Vale has pledged to reduce emissions from its own operations by 33% by 2030 and to become carbon neutral by 2050. The company has also committed to switch to 100% renewable energy in Brazil by 2025, and for its wider global operations by 2030.

Parcel delivery service UPS, for example, offers a carbon neutral option which supports projects that offset the emissions of a shipment’s transport. This includes investing in projects such as wastewater treatment, landfill gas destruction, methane destruction and reforestation.

Japan-headquartered industrial company Mitsubishi Heavy Industries has committed to reducing its GHG emissions by 50% from 2014 levels by 2030 – a target that includes its own direct emissions as well as the emissions that occur as a result of the company’s energy consumption.

MHI has also gone further by committing to reducing these Scope 1 and 2 emissions to net zero by 2040, ten years ahead of the Japanese government’s national target. The company has said it plans to do this by reducing emissions from its own plants and facilities, as well as capturing, storing and transporting CO2, including using carbon dioxide as a raw material for carbon recycling.

Smaller companies

But interest in carbon credits is not limited to the big emitters. Companies seeking to offset part or all of their emissions range in size from high street retail companies or restaurants to multinational integrated industrials.

Smaller companies tend to lack the sophisticated resources needed to identify, invest in or procure large volumes of carbon credits, and instead may approach brokers or other types of intermediaries to purchase credits on their behalf. Additionally, larger companies may buy credits on wholesale exchanges or use the derivatives market to hedge their positions as part of more complex risk management strategies.

Other organisations that may decide to buy carbon credits include not-for-profit organisations such as schools, colleges and universities, as well as government departments and state-run agencies seeking to demonstrate their contribution to wider efforts to reduce their negative environmental impact.

Why buy carbon credits at all?

Many of the large international bodies such as the United Nations have underlined the importance of companies reducing their own direct emissions first before turning to carbon offsets. However, cutting emissions to zero in the short-to-medium term isn’t always feasible, and carbon offsets provide a way to neutralise unavoidable emissions in a way that is both immediate and cost-effective.

In recent years, a number of press reports have surfaced claiming that some carbon reduction projects have been less effective in reducing emissions than their operators have claimed. While this can damage the reputation of the wider market for carbon credits, it also highlights the importance of companies investing only in projects that are credible, measurable, and independently verified by third parties.

To protect against reputational damage, buyers may choose a number of options, including doing their own due diligence, performing know-your-client (KYC) checks, researching the specific projects they are considering investing in, applying caution and being selective in their choice of project, and using the services of independent ratings agencies to gain insight into the level of risk presented by any given carbon reduction project.

Even though short-term market trends can drive interest up and down in carbon offsets, the long-term need to reduce GHG emissions to avert serious climate disruption — and the difficulty in reducing emissions to absolute zero – bodes well for demand for carbon offsets over the long term.