Nuclear power generation does not involve the burning of fossil fuels and has a key role to play in the ability to achieve global energy transition targets at least in the medium term as it complements renewables in the race to net zero greenhouse gas emissions. But Germany has shunned nuclear as part of its own energy mix, even while many mature and developing nations seek to invest in the technology to help piece together the clean energy supply jigsaw. Germany closed the last of its remaining nuclear reactors in April 2023, raising questions as to how it will manage to fully decarbonise.

Germany’s stated aim is to reach net zero by 2045, and the latest ambition for its energy transition policy (Energiewende) is for renewable energy, including wind and solar, to account for four-fifths of its power mix by 2030 compared with 47% in 2022. A completely renewable electricity system is envisaged by 2035, with mining of carbon-intensive lignite (brown coal), which is still a key foundation of Germany’s energy supply, to cease by 2038.

Nuclear often seen as part of the solution

Nuclear power is widely considered a clean energy as it does not produce greenhouse gases, nor local air pollutants such as mercury or soot, and is seen as complementing renewable sources. The International Energy Agency (IEA) puts global nuclear energy capacity at 413 gigawatts (GW), which it estimates averts 1.5 gigatonnes (Gt) of global GHG emissions and 180 billion cubic metres (bcm) of global gas demand. According to the World Nuclear Association[directory link], nuclear is the world’s second-largest low-carbon power, behind hydroelectricity, and accounted for just over one-quarter of total low-carbon energy supply in 2020. Nuclear also provides around 10% of total global electricity supply from 440 reactors.

While it does not classify as renewable, nuclear is still expected to be critical to ambitious global net zero emissions targets, particularly given its reliability compared with weather-dependent renewable energy sources such as wind and solar. However, the IEA estimates that investment in nuclear, which averaged $35 billion a year in the 2016-2020 period, needs to almost triple to $100 billion annually in the late 2020s if it is to play its role in the energy transition.

Germany parts way with nuclear

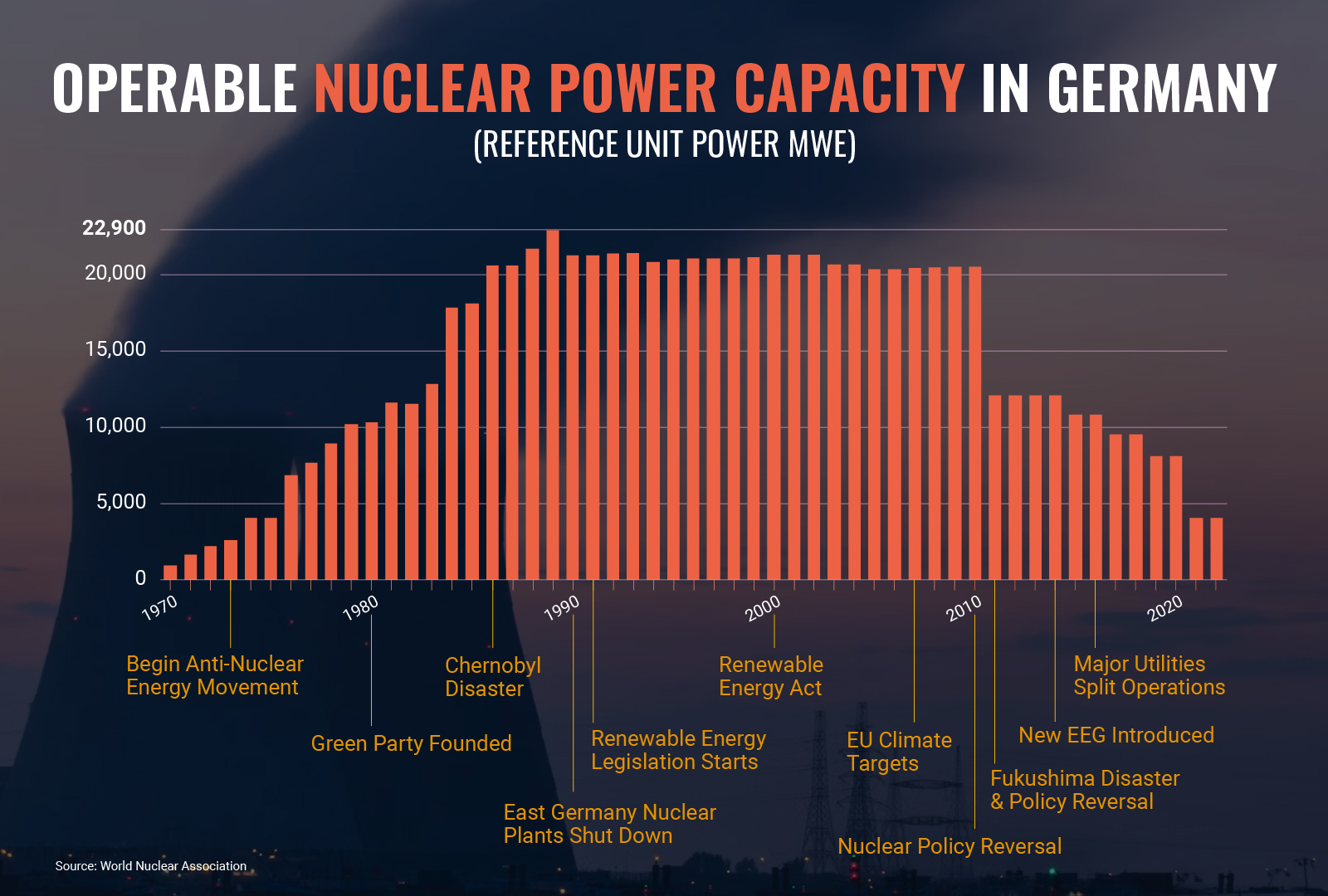

Certainly, nuclear was an important cog in Germany’s energy supply picture after capacity built up in the 1970s and 1980s, and at its peak in 1997 it accounted for almost one-third of total electricity production, second only to coal at almost 52%, with gas a distant third at nine percent.

However, many German citizens had deep-rooted concerns about the dangers of nuclear fission and, following the election of the Social Democrats and Green Party in 1998, the country announced plans to phase out nuclear energy. Although those plans stalled with a change in government, its share of the energy mix had fallen. That downtrend accelerated rapidly in 2011 with the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in Japan after a tsunami caused by a massive earthquake off the country’s north-east coast, which led to the release of radioactive materials into the nearby environment and leaks into the ocean. The accident prompted the immediate closure of eight German reactors in response to public fears over safety that had long existed before also the 1986 Chernobyl disaster in Ukraine. In 2012, nuclear accounted for a considerably smaller 16% of the country’s electricity production and just six percent in 2022.

As Germany continued to pursue an end to nuclear energy capacity, it closed the last of its remaining reactors in April 2023, a few months behind the end-2022 schedule as the energy crisis exacerbated in considerable part by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine reduced gas supplies from the former major source. The closure of the Nordstream pipeline supplying Russian gas to Europe meant nuclear was needed at least temporarily to fill gaps in the country’s energy provision as a major importer.

Nuclear still the option for many nations

While Germany’s anti-nuclear policies tend to grab the headlines, other mature economies, such as Belgium and Spain, also are looking to phase out usage. Taking the opposite stance, Britain and France and several developing countries plan to retain and expand nuclear power as part of their solution.

High capital costs and long lead times have tended to disincentivise investment in nuclear capacity, but small modular reactors (SMRs) are becoming increasingly popular as an option to replace old coal power plants. Smaller in size and power output, they are also cheaper and faster to develop at around three to five years, around half the time required for a large reactor.

Can Germany win the race against time?

Germany sees renewables as the answer and as part of its transition is ending brown coal mining by 2038, having until recently been the world’s largest producer of the material. Brown coal is more profitable than hard coal as it is used mainly in power stations in close proximity to the mines. However, it has a carbon content of 25-35% and is more CO2 intensive than hard coal. (Germany closed the last of its hard coal mines in 2018.)

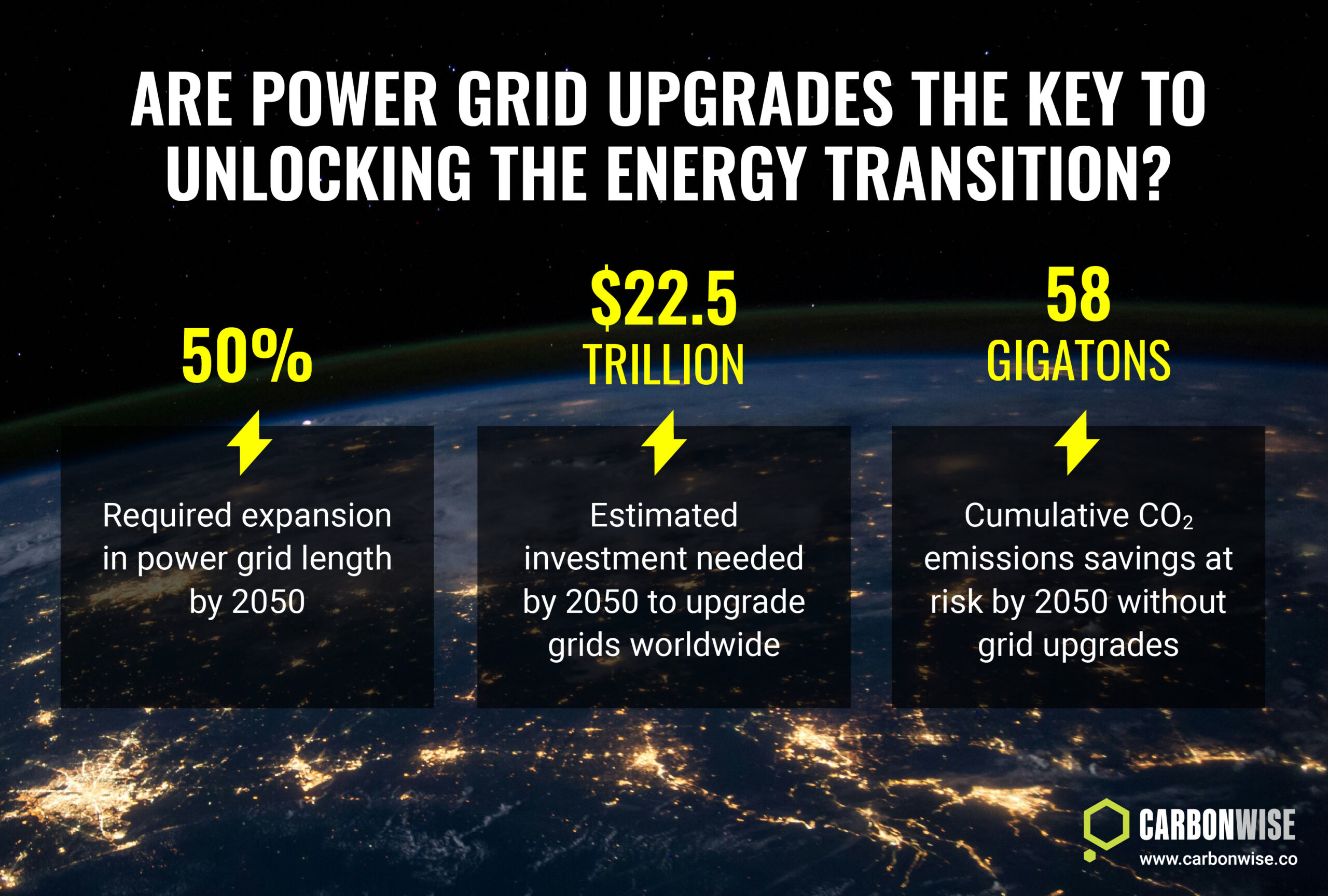

Germany is facing pressure to step up its investment in renewables. . Clean Energy Wire, citing a joint progress report by the German Association of Energy and Water Industries (BDEW) and consultancy EY, reported that the country needs investments of around 600 billion euros to achieve its 2030 energy transition target. The report said that one of the biggest obstacles was insufficient investment in renewables, stating that investment in photovoltaics needed to more than double and more than triple in onshore wind.

Part of Germany’s solution is also to cut energy consumption. In April 2023, the coalition government announced plans for a law requiring a 26.5% reduction in consumption by both the private and public sectors by 2030 from 2008 levels. The aim is to save 45 terawatt hours (TWh) annually. Non-binding targets were also planned for a 39% reduction by 2040 and a 45% cut five years later.

Clearly this would be significant, but Germany’s otherwise heavy reliance on weather-dependent energy sources is not without critics in a warming climate. Battery storage systems will be critical to the ability of renewables to account for a higher proportion of power systems. Furthermore, nuclear supply might also face problems and the possible negative impact of global warming on the reliability of nuclear as a power source must also be considered. Increased extreme weather events like storms and rising sea levels might threaten structures often located near oceans for the access to water. Nuclear plants also need large amounts of water for cooling such that drought conditions would also pose dangers.

As we look towards a future marked by the imperative of transitioning to clean energy, Germany’s ambitious strategy serves as a unique case study. By making a steadfast commitment to renewable energy, while simultaneously ruling out the nuclear option, the nation has set itself a challenging path. While some critics may argue that this approach is overly reliant on the capricious nature of renewable sources, it underscores Germany’s commitment to a future that not only aims for carbon neutrality but also prioritises safety and sustainability.However, the rate of investment in renewable sources clearly needs to be ramped up aggressively to keep pace with Germany’s goals. At the same time, the country’s commitment to drastically reduce energy consumption offers another crucial lever in its fight against climate change. It is a daunting task, riddled with uncertainties and potential pitfalls, but Germany’s endeavour, if successful, could provide a blueprint for a truly sustainable, non-nuclear path to net-zero emissions. As the world watches, the lessons we learn from Germany’s ‘Energiewende’ could potentially shape the future of global energy policies.