What are Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) in the context of the Paris Agreement on climate change? What do they do, and why do they matter?

NDCs are the climate commitments that governments submitted under the Paris Agreement, signed in 2015 by more than 190 countries. Almost all of them include a target to cut greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by a specified amount – usually a percentage reduction from a baseline set in 1990 or another year.

The NDCs are significant because the Paris Agreement for the first time included commitments to reduce GHG emissions by all countries, not just the wealthier industrialised nations, as was the case with the 1997 Kyoto Protocol.

Breaking the log-jam

This helped to overcome an impasse in the climate negotiations in which some wealthier countries objected to an earlier classification under the United Nations that meant fast-developing economies like China were not required to take on binding emissions reduction targets, even though their rising emissions threatened to eclipse reductions being made elsewhere.

As well as climate commitments such as specific emissions reduction targets, most governments also include a list of intended policies and actions in their NDCs that they intend to use to help achieve their overall target.

The NDCs communicated by each government are recorded in a public registry administered by the secretariat of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. This level of transparency helps to promote an atmosphere of trust between governments, with a widely-held expectation that countries will not backslide on commitments already made. While this trust can sometimes appear fragile, the atmosphere of cooperation has managed to survive thus far.

The role of Parties

The high-level engagement by political leaders and heads of state at the annual United Nations climate summits also helps to send a signal to the private sector about the overall intended direction of travel with regards to climate policy.

This becomes all the more important when crafting specific policies that affect companies in the high-emitting sectors such as energy, industry, manufacturing, transport and agriculture. With specific policies in place, companies can make sustainable investments with greater confidence in their long-term viability.

A look at the NDCs submitted by major economies provides some insight into their respective targets, as well as national challenges faced with regard to climate change and the energy transition.

USA

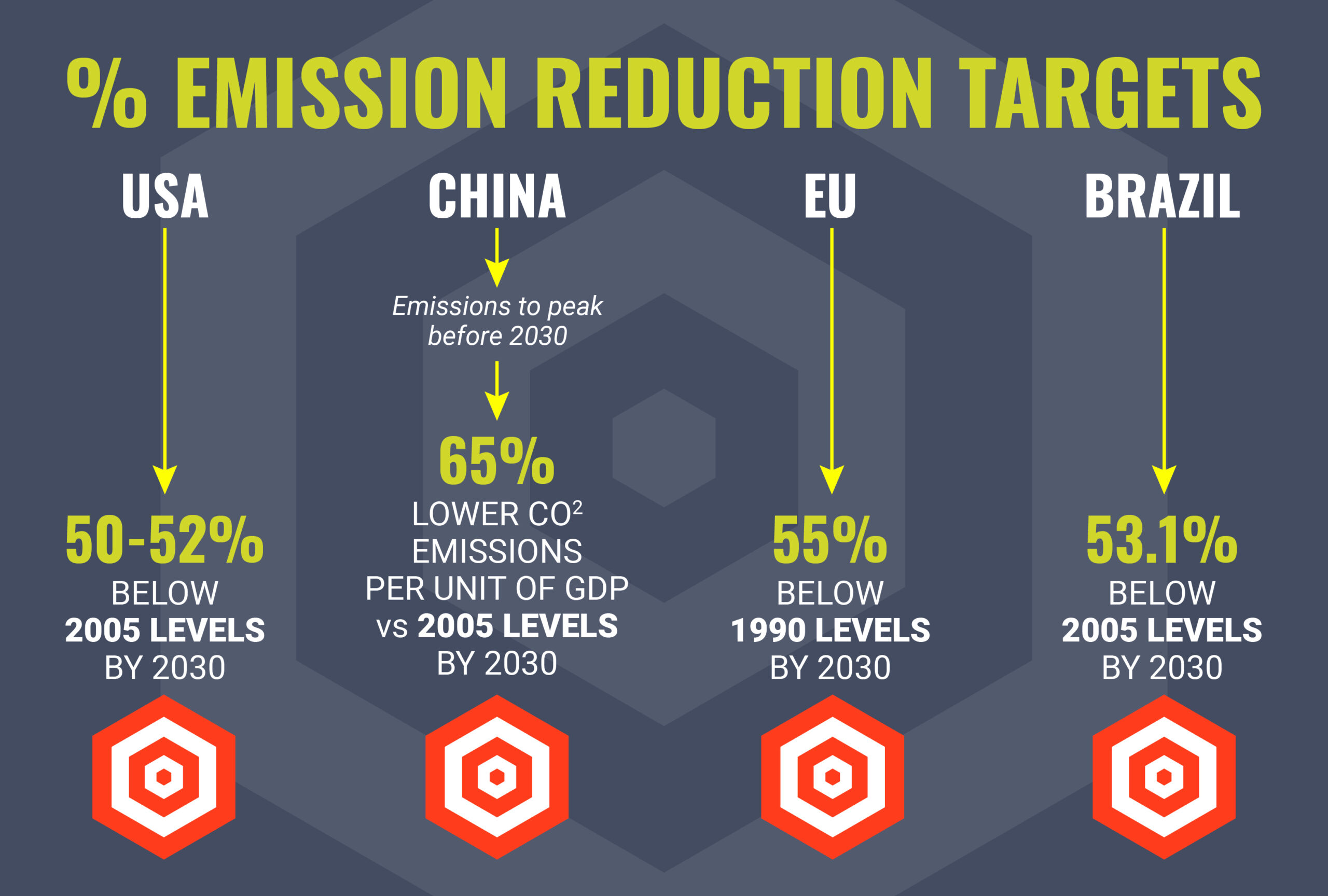

The USA, for example, set a target to cut GHG emissions by 50-52% below 2005 levels by 2030, with an interim target to cut them by 26-28% by 2025.

America’s emissions peaked in the early 2000s and have been falling since. This is due to a number of factors, including the rise of renewable energy. States such as Texas have pioneered the use of wind to generate electricity, for example. In 2020, America generated approximately 19% of its total electricity use from renewable sources, according to its NDC document. Including other carbon-free sources, the figure was 39% in 2020.

However, America’s success in bending the emissions curve downwards has also come about through improvements in other technologies. Advancements in horizontal drilling techniques allowed the USA to ramp up its domestic production of shale gas, for example. This led to falling prices for natural gas in America, helping the cleaner fuel displace more emissions-intensive coal for power generation, reducing the country’s GHG emissions.

America’s stated approach to climate policy includes working with state, local and tribal governments on measures to encourage the uptake of clean energy generation, including renewables, nuclear and retro-fitting existing installations with carbon capture technology. Other policies include transport measures such as standards for tailpipe emissions and efficiency, and incentives for zero-emissions vehicles and low emissions fuels.

Continued success for America will depend on the achievement of similar scale emissions reductions in other sectors such as heavy industry, transport and agriculture. In its NDC, America formally recognised the job-creation potential of deploying zero-carbon solutions at home, as well as achieving additional benefits such as a reduction in local air pollutants due to a shift away from high-emissions fuels.

China

Rising economic powerhouse China’s NDC consists of a target to have GHG emissions peak before 2030 and to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. The country also committed to lower CO2 emissions per unit of Gross Domestic Product by over 65% from 2005 levels and to increase the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to around 25% by 2030.

China also set targets to increase its forest stock volume by over 6 billion cubic metres from 2005 levels and to bring its total installed capacity of wind and solar power to over 1.2 billion kilowatts by 2030.

In its NDC documents, China highlighted the challenges it faces in achieving its climate goals, pointing to a need to develop economically in a country with a population of 1.4 billion. China is also rich in coal – the most emissions-intensive of the fossil fuels – and poor in oil and gas, making the energy transition more challenging than in many other countries.

European Union

The European Union, consisting of 27 member states, committed to reduce its GHG emissions to at least 55% below 1990 levels by 2030 – one of the most ambitious targets of any region in the world. Recognising that member states have differing dependencies on emissions-intensive fuels for power generation and industry, the EU pledged to work to achieve the overall target collectively, while pursuing EU-wide policies as well as those in place at the national level.

Policies to achieve the EU’s goal include the EU Emissions Trading System, which regulates CO2 emissions from electricity generation, heavy industry, manufacturing and aviation, as well as collective legally binding targets to increase installed capacity of renewable energy (the Renewable Energy Directive) and boost energy efficiency (Energy Efficiency Directive) and a host of other policies including those targeting emissions from transport, buildings and land use. These are grouped under the EU’s so-called “Fit for 55” legislation which aims to enable all sectors of the economy to help deliver the 55% emissions reduction goal.

Brazil

Brazil is an example of another developing country with a fast-growing economy, huge landmass, and a rich supply of natural resources. Under the Paris Agreement, Brazil committed to reducing GHG emissions by 37% from 2005 levels by 2025 and by 50% by 2030. The country considers that this target exceeds the level of ambition expected of a developing country with a relatively low contribution to historic GHG emissions.

Brazil’s government underlined that it already has one of the cleanest energy mixes in the world, with renewables accounting for 48.4% of total energy demand in 2020 – three times the world average. This includes hydropower, which accounts for 60% of the country’s total installed electricity capacity.

And in the land use sector, the country has deployed the Low Carbon Agriculture Plan, which has channelled R$17 billion (US$3.47 billion) into areas such as recovering degraded land, forest planting and agroforestry, and the integration of forest, crops and cattle breeding. Brazil’s massive agriculture sector has also enabled it to become a major world producer of cleaner fuels, for example biofuel for transportation, that can reduce emissions far beyond the country’s borders when displacing fossil fuels.

An evolving space

NDCs are the ‘bread and butter’ of the Paris Agreement, and the targets and action plans they contain are vital parts of the overall effort to bring down atmospheric concentrations of GHGs to avoid catastrophic climate change. But what matters even more, perhaps, is how much further governments can go by including new and revised emissions reduction targets in their NDCs, as well as more ambitious policies to further drive the clean energy transition forward and to close the gap between where emissions are today and where the science says they need to be.