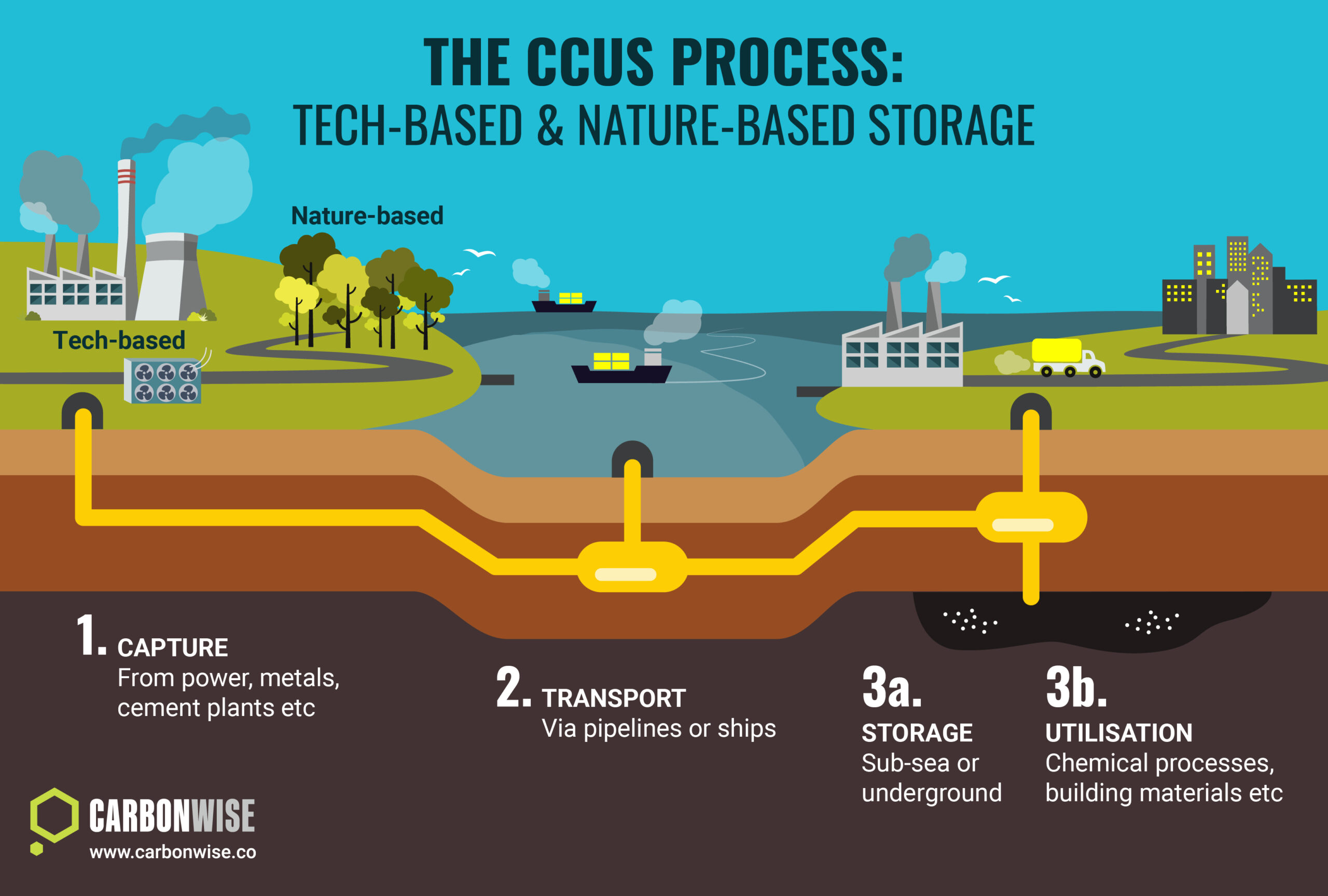

Carbon removals are activities that remove carbon emissions (carbon dioxide) from the atmosphere and store them away (in rocks, underground or in vegetation) so that they no longer form part of our atmosphere.

Removals are distinct from other types of carbon credit projects. Where carbon credits typically represent avoided carbon emissions, or reductions compared to business-as-usual, removals actively reduce the total amount of greenhouse gases (GHGs) in the Earth’s atmosphere. As such, carbon removal projects have a vital role to play if we are to hold “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels,” as set out in the Paris Agreement adopted following the 21st United Nations Conference of Parties in the French capital in 2015.

One way to consider the difference is to picture the atmosphere as a bathtub being filled. The water flowing in through the taps represents emissions of GHGs, which are now reaching levels that threaten to overflow the tub.

Carbon reductions can be represented by turning off the taps so that no additional GHGs are vented into the atmosphere. However, this does not address the total of GHGs already present – the full-to-overflowing bathtub.

Carbon removals can be represented by pulling out the plug and draining some of the water from the tub, which in carbon terms, lowers the concentration of GHGs in the atmosphere.

Removals’ Vital Role

Merely reducing annual global emissions won’t be enough to keep temperatures within this crucial threshold; the total amount in the atmosphere needs to fall. As such, The Oxford Principles for Net Zero Aligned Carbon Offsetting state that “users of offsets should increase the portion of their offsets that come from carbon removals, rather than from emission reductions, ultimately reaching 100% carbon removals by mid-century to ensure compatibility with the Paris Agreement goals.”

However, the biggest problem currently facing any company or government’s efforts to increase their exposure to carbon removals is the acute shortage of projects generating purchasable removal credits. Taking emissions out of the atmosphere is a technically complicated and expensive process, and credits from the few projects currently qualifying as carbon removals cost hundreds of times more per ton than credits from emissions avoidance projects.

A huge amount of capital is therefore needed to develop these nascent technologies to ensure there is sufficient supply to meet the inevitable surge in demand in the coming years. This dynamic could see carbon credits climb to above $250 a ton in a market worth $1 trillion a year, according to BloombergNEF.

Different types of carbon removal projects

Carbon removal projects can be divided into six different areas:

1. Ocean-based

2. Reforestation

3. Soil (regenerative agriculture, for example)

4. Biomass

5. Direct Air Capture

6. Rocks (enhanced rock weathering)

Of these, the ocean has the greatest potential, since the seas already act as the world’s biggest carbon sink. Technologies such as electro-chemically treating seawater are still in their infancy, however.

The biomass sector, specifically biochar, charcoal created by heating agricultural waste, is the biggest source of present-day removal solutions. As biochar decomposes much more slowly than the original biomass used to make it, the method was recognised as an official carbon sequestration source by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2018.

Since then, its popularity has soared, as biochar not only sequesters three tons of carbon for every ton of biochar produced, but it also has practical uses as a soil improver or as a building material.

But the sheer quantity of carbon emissions needing to be removed to keep the planet within acceptable levels of warming means we need “climate action on all fronts: everything, everywhere, all at once” as the United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres said.

Technology Race

While biochar has the potential to sequester 2 billion tons annually by 2050, that’s still only a tenth of the 20 billion tons the IPCC estimates will need to be captured from the air and stored by 2050. Given the scale of the problem, as well as the potential rewards for success, it is unsurprising to see some of the world’s richest investing in removals technology.

Elon Musk set up the XPRIZE Carbon Removal in 2021, which offered a $100 million purse to incentivise entrepreneurs to develop scalable removals technology by 2025. Microsoft has also been very active in the sector, agreeing Direct Air Capture deals with CarbonCapture and Climeworks, investing in ocean-based solutions with Running Tide and a carbon capture and storage partnership with Danish energy giant Orsted.

Tech giants Stripe and Google are among the companies backing the Frontier Carbon Removal Fund, which is aiming to spend about $1 billion on carbon removal projects, including a recent deal with Charm Industrial to remove over 100,000 tons of carbon between 2024 and 2030 via its biomass-based solution.

A Ton Removed

As well as the necessity of the work, carbon removals have the added attraction of being able to quantify exactly the amount of carbon dioxide extracted from the atmosphere and are much less open to conjecture than projects in other parts of the offsetting world.

The permanence of carbon removals, in contrast to the risks associated with factors like forest fires or the potential scrutiny of emission avoidance calculation methodologies, makes the sector appealing to companies seeking to avoid accusations of greenwashing.

However, this certainty comes at a cost, with removals projects currently costing in excess of $100 a ton and some credits even costing as much as $600. Investing in carbon removals technology and its projects remains purely voluntary at this point, and these figures compare poorly with less than €100 a ton for an allowance in the European Union’s Emissions Trading Scheme, a compulsory requirement for the bloc’s heavy industrial sectors.

Yet investment in removals is essential to scale up sufficiently and rapidly enough to ensure we have the vast array of carbon-sequestering projects needed, both from a scientific and upcoming corporate demand perspective. And the hope is that with this scaling up, the average price of a credit comes down, making it more affordable to a broader array of companies.