The world of carbon offsetting has come under attack from many sides, with some critics describing the voluntary carbon market as nothing more than ‘greenwashing’ – allowing corporate polluters to make dubious claims over their sustainability while continuing to pursue fossil fuel-powered business models.

Some observers have warned that carbon offsetting is a dangerous distraction from the need to move beyond polluting fuels and to drive a revolution in clean energy, transportation, industry and agriculture, to avert catastrophic damage from climate change.

While some of these criticisms may be well-founded in respect to certain projects and approaches to carbon offsetting, they miss the real value that the voluntary carbon market can deliver: specifically, that putting a price on carbon can channel much-needed finance into keeping forests standing where they would otherwise be felled, rejuvenating degraded mangrove swamps and peat bogs to boost carbon sequestration, and improving the health of people in developing countries by supplying clean, efficient cookstoves, among many others.

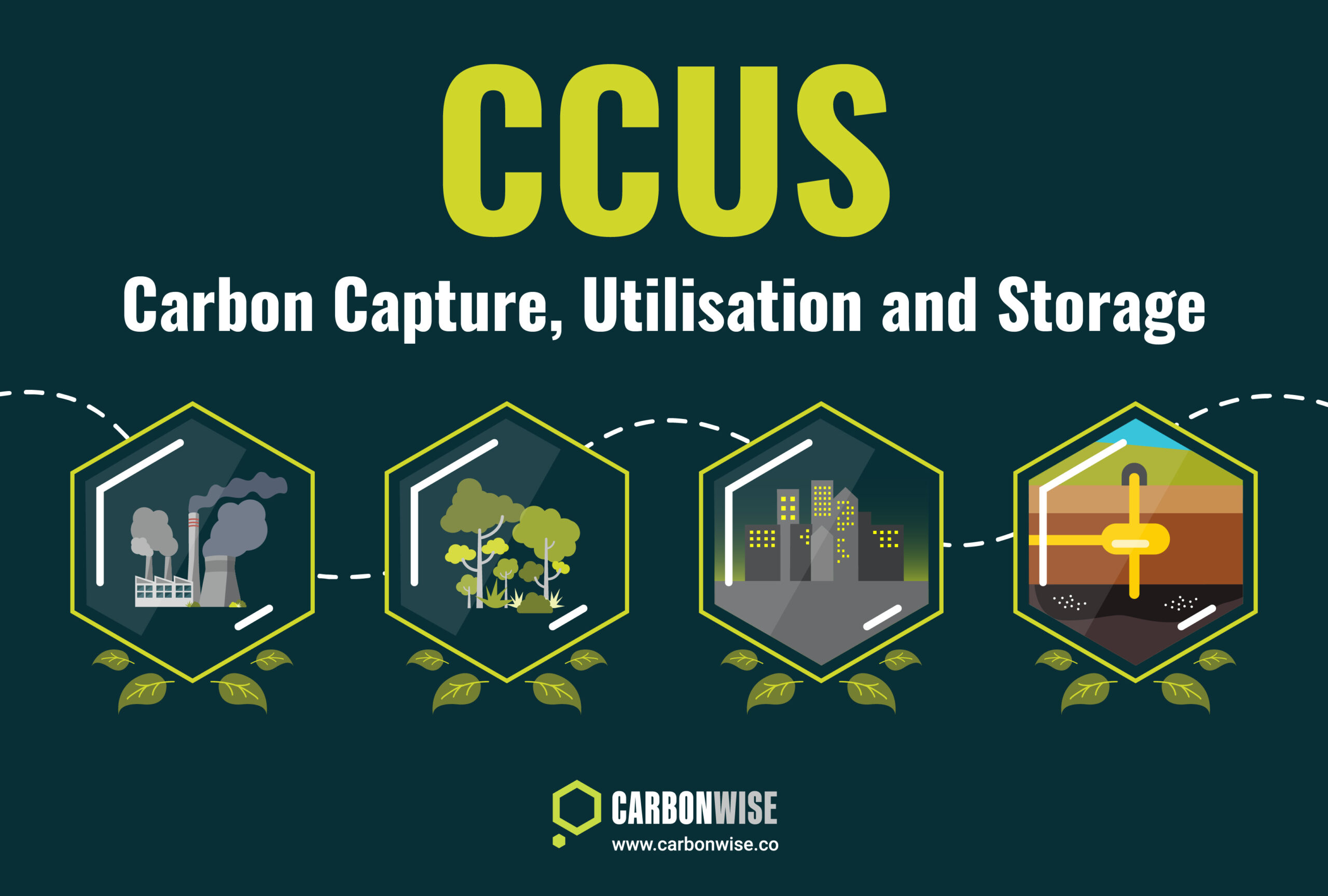

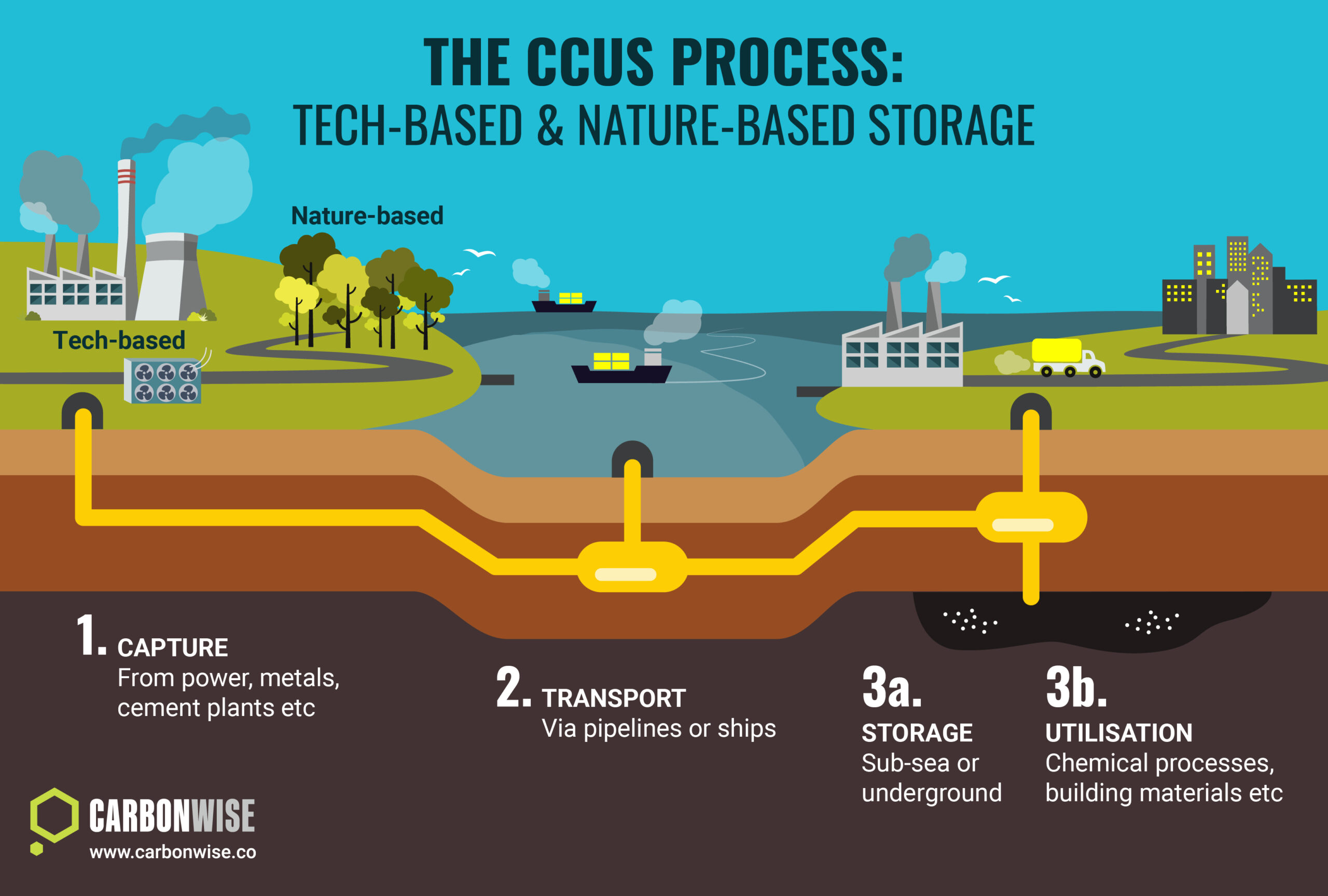

Carbon offsetting is an important plank in wider global efforts to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. However, many international groups including the United Nations and others emphasise that offsetting should take a secondary role to companies and governments directly reducing emissions. Direct carbon ‘removals’, such as the use of technologies that capture and store carbon from the air, will also play a vital role in bringing down the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide. By offsetting emissions that cannot be reduced, this flexible approach offers a realistic roadmap to reaching the net-zero target.

So what are the common criticisms made against carbon offsetting?

An unregulated market

One of the main concerns about carbon offsetting is that the market is unregulated. Unlike the legally binding carbon compliance markets, there is no overarching body that has the legal power to rule out certain kinds of carbon offsets. This means the voluntary market is self-policed by corporate emitters and the non-governmental organisations that create the standards that underpin the carbon reduction projects.

An important step in boosting the market’s credibility has come as a result of the carbon offsetting standards organisations making their methodologies public, allowing full scrutiny over how projects can qualify to earn carbon credits. As this work has expanded, the methodologies have been revised and improved over time.

Another way to address this lack of regulation is that projects must be verified independently by third parties, adding another safety layer to help prevent bad practice.

The ’wrong’ approach

Some organisations in the energy and climate space have said carbon offsetting is a distraction from more direct approaches that are needed to achieve a clean energy transition at pace and scale. While direct reductions are absolutely needed, if done properly, carbon offsetting can lead to real carbon reductions elsewhere at a lower cost than internal reductions alone, lowering the total bill for addressing climate change.

Bodies such as the United Nations and the International Organization for Standardisation (ISO) have said they prefer that companies focus on reducing their own emissions before turning to the use of offset credits. This approach has also been adopted by the European Union under its legally binding carbon compliance market, the EU Emissions Trading System, where the use of carbon offsets was phased out after 2020.

Offsets ‘are not real’

Some groups have claimed that carbon offsetting does not represent real emissions reductions and simply displaces emissions from one location to another. However, this is not an accurate portrayal of what’s taking place on the ground.

Consider an example where a logistics company operating a diesel-powered fleet of trucks in Germany wants to offset the company’s emissions by investing in a reforestation project in Honduras. Under this scenario, the baseline involves measuring emissions from the trucks in Germany and from an area of degraded forest in Honduras.

Under the carbon project, the land is reforested, absorbing CO2 directly from the atmosphere as the trees grow. If the cost per tonne of removed carbon in Honduras is lower than the cost per tonne of switching to cleaner transport fuels, the company has an incentive to buy credits from the project and claim the emissions reductions. Without the project, emissions would continue from the diesel trucks, and no removals would take place at the site in Honduras. By linking the two, the German company can offset its emissions by paying for and retiring the carbon credits.

And further side benefits can be delivered through the forest’s positive impact on biodiversity, for example. Monitoring the forest’s growth and ensuring it remains protected also offers employment for local communities, generating economic benefits.

Additionality

Another one of the key elements that has contributed to undermining the credibility of carbon offsets is the lack of what is called “additionality”. Additionality refers to whether a project is reducing emissions compared to what would have happened under a business-as-usual scenario.

There have been difficulties and uncertainties in establishing clear benchmarks from which to judge additionality, for example.

The main standards bodies that develop carbon reduction project methodologies have made strenuous efforts to monitor for additionality when setting baselines for projects. Moreover, as renewable energy has become more mainstream, the voluntary carbon market has begun to move away from renewables and to place more emphasis on genuinely new carbon reductions in sectors that would not otherwise take place without carbon finance. That’s because renewable energy projects are now cost-competitive against legacy thermal power generation in many instances, meaning they have lost their claim to be additional except in some lower income countries.

Permanence

A further criticism levelled at carbon offsetting is that the carbon reductions claimed by some projects are not necessarily permanent. For example, when destroyed by a wildfire, an area of forest ringfenced as a carbon sink project would immediately release the carbon back into the atmosphere, removing its environmental benefit at a stroke.

The standards bodies involved in the carbon credit markets have sought to address this problem by requiring that forest projects maintain a “buffer pool” of credits that all project developers must contribute to – effectively an insurance policy against project failure. In the event of a so-called ‘reversal event’ like a wildfire, an equivalent volume of credits would be permanently retired from the pool and taken out of circulation in the market, thus ensuring that the unintended release of carbon was properly accounted for.

Double counting

A further criticism of carbon offsetting is that without appropriate safeguards, emissions reductions could be counted more than once or claimed by more than one entity, undermining the environmental integrity of the underlying projects.

The main standards agencies in the voluntary market have worked to ensure that once a carbon credit has been retired, it can no longer be used. Moreover, more than 190 countries that signed the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change have said they want the future system of international carbon trading to ensure that double counting does not take place.

A race for integrity

While some of the criticisms levelled at carbon offsetting may be justified, a vast amount of work is underway to address those problems. This is becoming more urgent as the size of the market is likely to need to expand by a factor of at least 15 by 2030, and potentially much more by 2050.

The Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market – an independent, private-sector initiative – has said a high integrity voluntary carbon market is a “key complementary tool to reduce and remove emissions above and beyond what would otherwise be possible and to channel finance towards climate resilient development.”

A well-functioning voluntary carbon market can drive billions of dollars from companies emitting carbon to those removing it or reducing its release, the IC-VCM has said.

The IC-VCM also seeks to establish a set of Core Carbon Principles which will set new threshold standards for high-quality carbon credits, and it will also provide governance and oversight over the standard-setting organisations that underpin the voluntary carbon market.

The challenge for the voluntary carbon market is stark: fail to address environmental integrity and risk a reputational problem for thousands of companies generating, trading, investing and retiring carbon credits. Get the rules right, and help build a scalable tool that can play a major part in a global success story by channelling significant finance to sustainable energy, industry, transport, forests, and coastal and marine ecosystems, in a bid to reach net-zero emissions by mid-century, thus staving off the worst effects of climate change in the run-up to 2100.