The idea of carbon border charges has garnered plenty of attention in recent years, particularly as the European Union rolled out its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) in 2023.

What is a CBAM? Why are policymakers deploying this tool? What does it aim to achieve? And what are the expected impacts? In this article, we aim to address all these questions.

What is a CBAM?

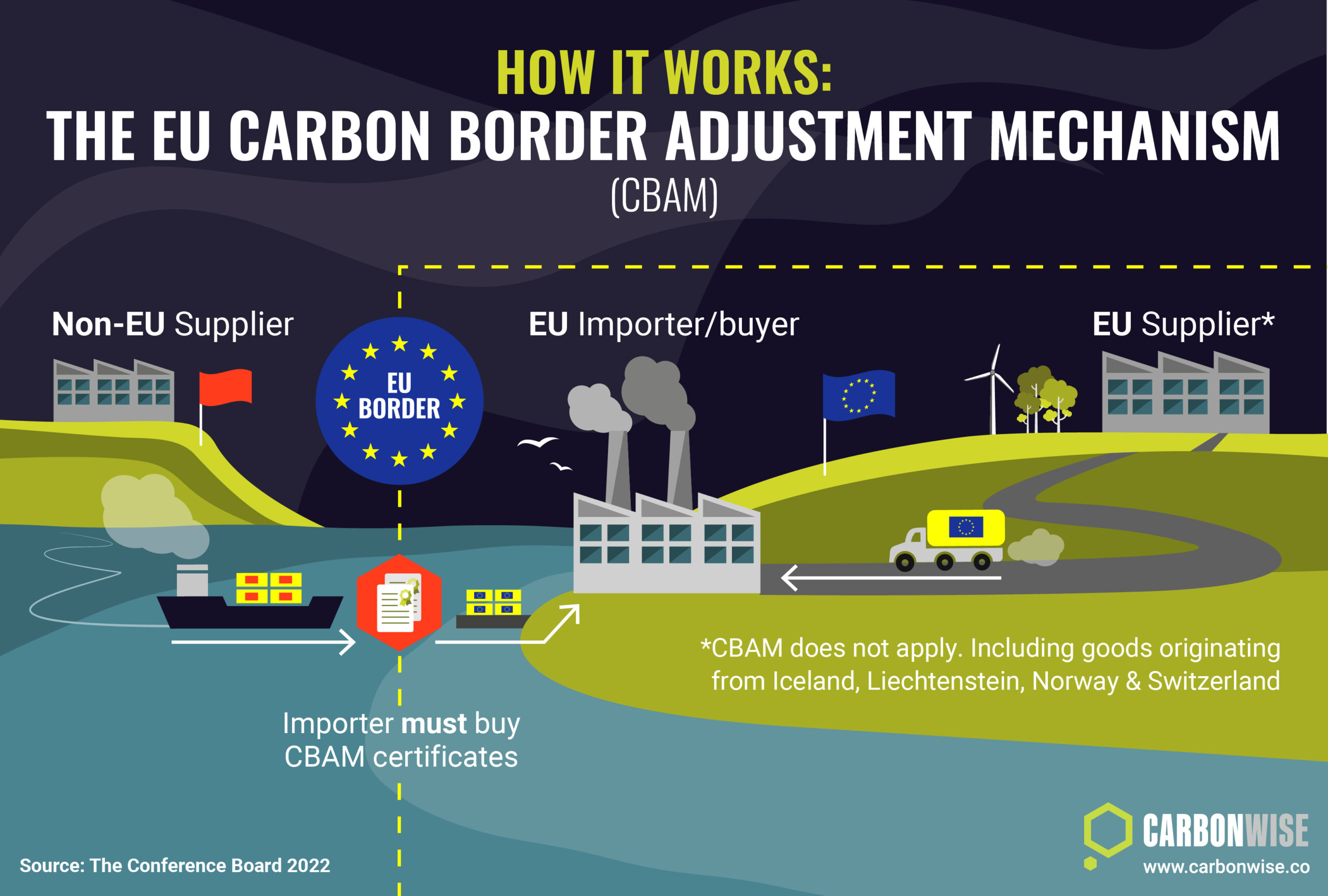

A Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism is a policy which aims to level the carbon costs of goods made in one jurisdiction with those produced elsewhere. To achieve this, a CBAM places an explicit cost on the carbon content of certain goods being imported into a country or region. In general, the goal of a CBAM is to prevent competitive disadvantages for companies in sectors exposed to a legally binding carbon market (an emissions cap-and-trade system), which can arise when companies import goods from other regions where no such carbon costs exist.

What is the EU’s CBAM?

The European Union CBAM entered into force on May 17, 2023, and its stated goal is to put a fair price on the carbon emitted during the production of carbon intensive goods that enter the EU. This is to protect EU-based industries from unfair competition, and to encourage lower-carbon production in other countries.

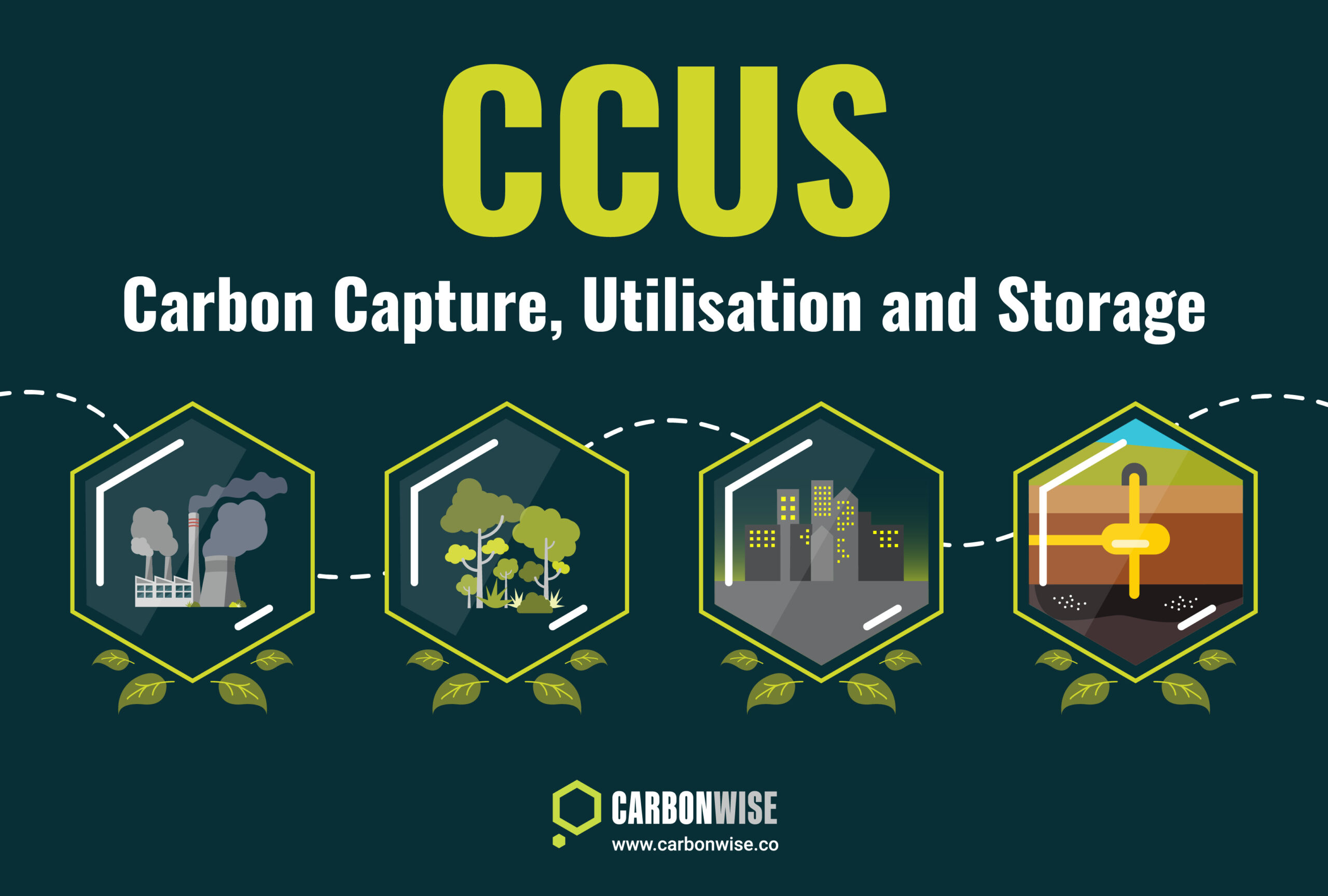

The CBAM will put a price on the CO2 emissions from specific sectors, such as iron and steel, cement, aluminium, fertilisers, electricity and hydrogen, and certain goods made from these materials. These are the sectors considered most at risk of ‘carbon leakage’ – the movement of emissions from one location to another, due to climate policy asymmetries. Carbon leakage can happen when a company shuts down operations due to carbon costs in one location and moves operations elsewhere, or changes a supplier so that goods are imported to circumvent the carbon costs due in their jurisdiction.

These carbon-intensive industries in Europe are exposed to global competition from other regions such as China, India, Brazil, Canada, South Africa, Russia, Turkey, the US and other major exporters of carbon intensive goods. This meant that exposing these EU-based industries to the full price of carbon under the EU Emissions Trading System could have put them at a competitive disadvantage. To mitigate this risk, many of these sectors were granted free carbon allowances under the EU ETS. However, this caused a problem of its own: giving allowances for free meant there was little incentive for these sectors to reduce CO2 emissions.

Since EU regulators want all sectors of the economy to contribute to long-term emissions reduction targets, something had to change. The EU’s CBAM provides a way to phase out free carbon allowances for industry, creating a stronger incentive for industrial companies to reduce emissions, while also protecting them from competitiveness issues linked to carbon costs.

How will the EU CBAM be implemented?

The CBAM is an EU Regulation (rather than an EU Directive), which means that it takes effect immediately in all EU member states.

A transitional phase will apply for the EU CBAM from October 1, 2023 until December 31, 2025, followed by a full implementation phase from January 1, 2026 until the end of 2034.

Reporting of CO2 data under CBAM is required on a quarterly basis. The first reporting period ended on January 31, 2024. This will change to annual reporting after the transitional phase ends in 2025.

A phased-in approach

The implementation phase of CBAM will be phased in gradually over several years, meaning importers will initially only need to surrender certificates for a proportion of the embedded CO2, and this will rise over time, accompanied by a gradual phasing out of free carbon allowances to industries under the EU ETS.

The phasing in of CBAM is designed to allow for a predictable and proportionate transition for EU and non-EU businesses. In the transitional phase, companies do not have to buy or surrender CBAM certificates, and only need to report data on the CO2 content of their relevant imports. However, once the full implementation phase begins in January 2026, companies importing CBAM-related goods will need to buy CBAM certificates and surrender them every year.

Exemptions

Imports from certain countries will be exempt from the EU CBAM. These include Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein, as these non-EU countries already participate in the EU ETS, and Switzerland, which has its own domestic emissions trading system which is linked to the EU scheme.

How will CBAM certificates be distributed and priced?

Companies importing CBAM-related goods will be able to purchase CBAM certificates from the European Commission through regular sales, and these will be tracked in a centralised registry.

The price of CBAM certificates will be calculated using the average weekly auction price of EU Allowances (EUAs) under the EU Emissions Trading System, expressed in euros per metric ton of CO2 equivalent (Euro/mtCO2e). The European Commission will publish the average auction price of EUAs on the first working day of the week for the previous week of auctions, and this will determine the price of CBAM certificates for that week.

CBAM certificates will not be directly linked to the EU ETS, and the two instruments are not fungible – that is, CBAM certificates cannot be used to comply with the EU ETS, and EU Allowances cannot be surrendered to meet CBAM obligations.

The CBAM certificate price will simply mirror the EU Allowance price. This is to ensure that the cost of CBAM certificates is closely linked to the price of carbon that EU-based companies must pay at any given time, levelling the cost of carbon inside and outside of the EU for affected industries. CBAM certificates are not designed to be tradable. Upon sale, each CBAM certificate will be stamped with a unique identification code which includes the price paid and the date of the sale.

Compliance

After the transitional phase, companies affected by the CBAM must surrender by May 31 each year a number of CBAM certificates equal to the verified carbon embedded in their imports of CBAM goods in the previous calendar year. The certificates must be submitted to the relevant national competent authority. The first compliance deadline is May 31, 2027, for the reporting year 2026.

Companies that fail to comply with the CBAM reporting requirements, or who include inaccuracies in their reports, will face fines set by each EU member state, of between €10 and €50 per mt of CO2 equivalent.

Companies that fail to surrender sufficient CBAM certificates to match the verified carbon content of their CBAM imports will face a fine of €100 per mt of CO2 equivalent for every ton not covered by a certificate. This fine is equivalent to sanctions imposed for non-compliance with the EU ETS.

Expected impacts

The impacts of CBAM can be considered in two distinct categories: ‘first-order’ impacts which relate to the immediate ramifications for companies involved, and ‘second-order’ impacts which include the longer-term structural changes that could result from the CBAM.

The rollout of the EU’s CBAM transition phase, which started in 2023, means that EU-based companies must get to grips with the data reporting requirements, and be able to demand relevant data from their supply chain partners. This means that the data reporting obligations extend to companies outside of Europe too.

First-order impacts

The immediate effects of the CBAM transitional phase include the legally-binding reporting requirements for EU-based companies importing CBAM-relevant goods. This means companies will need to provide data on the embedded carbon content of these goods, and they may need to pressure their supply chain partners to do the same, or face penalties for non-compliance. Once the full implementation phase begins in 2026, these companies will need to buy CBAM certificates.

These impacts also extend to companies outside of the EU who are exporting carbon-intensive products into the bloc. They too will need to provide data on the carbon content of their exports and they will need to be able to track CO2 values from the production of these materials all along the supply chain, which may involve producers, intermediaries and specialist handlers of goods.

In many cases, this is likely to mean that supply contracts will need to be amended to specify the obligation to provide this embedded CO2 data along with the products sold.

Second-order impacts

In the longer-term, the rollout of the EU’s CBAM has several potential implications. EU-based companies importing iron and steel, cement, fertiliser and the other CBAM goods, may begin to source materials from companies able to produce these materials in a low-carbon or zero-carbon process, if the cost is lower than paying for CBAM certificates. This could drive decarbonisation across the world as companies compete to provide the lowest-carbon version of goods for export to the EU. The explicit cost of CBAM certificates is likely to focus corporate minds on finding ways to reduce emissions, whether those are incremental efficiency improvements or breakthrough technologies, for example switching from steel made in a traditional blast furnace to electric arc technology.

Another possible impact is that some EU-based companies that until now have imported CBAM-related goods may find it is more profitable to buy them from EU-based producers, thus avoiding the need to pay for CBAM certificates.

In addition, CBAM costs will be lower for imports from countries where a price has already been paid on the carbon content of goods produced. If this cost is lower than the EU carbon price, the payable CBAM charge will be the difference between the two. This is likely to encourage other countries to adopt domestic carbon pricing systems, as it will help their exporting companies to cut the cost of their products for EU-based buyers.

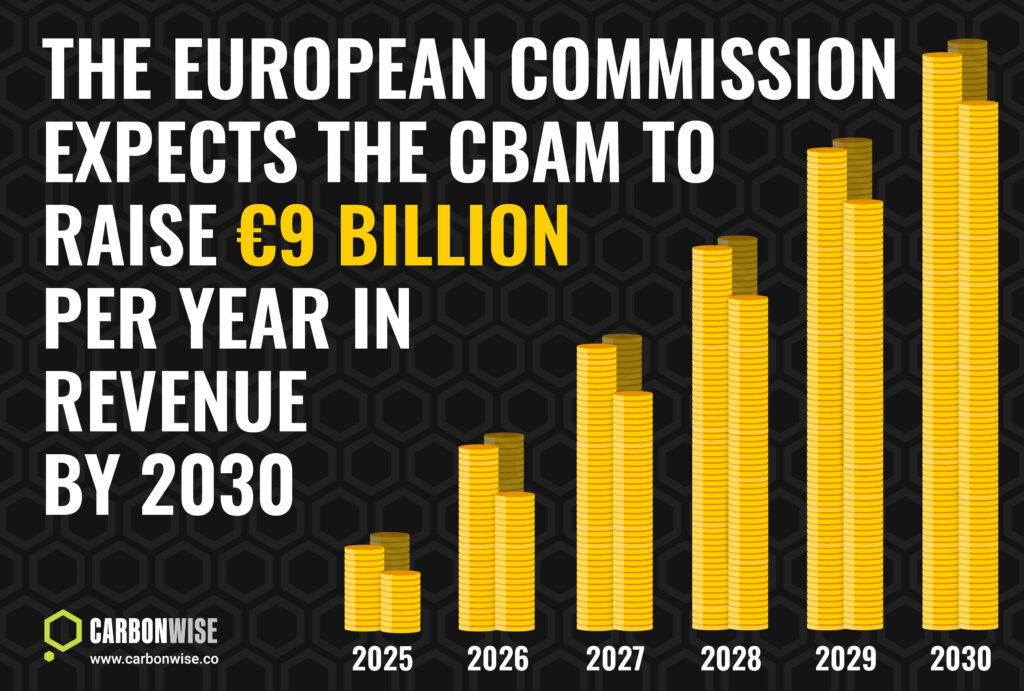

The European Commission has estimated that the total revenues earned by the CBAM will reach just over €9 billion per year by 2030. By 2040, this figure could be much bigger.

One outcome of this change in carbon economics is that companies exporting CBAM-covered goods from particularly CO2-intensive economies may find it much harder to compete with those producing the same products in a cleaner way. This could reduce demand for Chinese goods and increase demand for US exports, for example, as American companies can produce most of the CBAM goods at a lower carbon intensity than their Chinese counterparts.

Other countries are already considering deploying their own CBAM policy. The UK for example, plans to roll out a domestic carbon border charge in 2027.

India, meanwhile, is considering an exports tax on products covered by the EU’s CBAM. This would be equivalent to the cost of CBAM certificates, meaning that Indian exports to the EU could be exempt from the CBAM. Other countries could follow suit, particularly if such a carbon tax would be simpler to administer than a domestic emissions cap-and-trade program.

Challenges to CBAM

The EU’s rollout of CBAM is likely to face some hostility, potentially within and outside the World Trade Organisation. South Africa has called the policy discriminatory while China has raised concerns at the WTO. The EU, for its part, has said it designed the CBAM specifically to be WTO-compatible by avoiding any discriminatory elements. More of this will become clear as the EU’s CBAM transitions to its full implementation phase.

Extending the CBAM

In addition, the EU is considering extending the CBAM to other sectors of the economy, and this could have a similar impact on other products. Any such extension is a political decision and it remains to be seen which sectors might be added to the EU CBAM’s scope. But potential sectors that could be covered include refineries, glass, pulp and paper, bricks, ceramics, acids and bulk organic chemicals.

Wider significance of CBAM

The EU’s CBAM represents the convergence of two important multilateral issues: trade and climate. The policy will enforce a new and more urgent focus on data reporting processes covering embedded CO2 in products in the EU and beyond, and it will change the economic calculus for carbon intensive goods versus their lower-carbon alternatives. The policy is likely to trigger further hostility in some quarters, but it will also prompt the emergence of new carbon pricing policies outside of Europe, and this is likely to lead to greater domestic carbon taxation policies around the world. In the main, this is because non-EU governments are likely to want revenue to stay in their own country, rather than be paid to EU regulators. This may end up driving domestic carbon tax policies as a way to make exports exempt from the EU CBAM.