As had been widely predicted, returning President Donald Trump formally signed an executive order withdrawing the United States from the Paris Agreement in the first week of his presidency.

The Paris Agreement is a globally inclusive climate treaty which almost all countries have signed. The agreement requires governments to contribute national targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions which become more stringent over time, to limit the more destructive physical impacts of climate change.

While it’s common knowledge that President Trump signed an identical order in 2017 shortly after he arrived in the White House for his first term in office, what’s not widely understood is that the US did not quit the Paris treaty until the day after the 2020 election – in which he was defeated by Joe Biden.

The delay was due to Article 28 of the Paris Agreement, which states that member countries cannot leave the pact within the first three years after they have signed up to it.

Consequently, the US did not formally leave Paris until November 4, 2020. And by February 19, 2021 – just 107 days later – President Biden had brought the US back into the fold.

But this time, the US only has to give one year’s notice, so the US will continue to participate in all the Paris Agreement activities – including this year’s COP – before its withdrawal takes effect in a year’s time.

With so little experience, it’s very difficult to work out what the impact of the US leaving the Paris Agreement will be.

There are relatively few concrete elements that we can assume. Firstly, the US will not be bound to meet its Nationally Determined Contribution – its climate pledge – that was submitted to the UN just last month.

In the NDC document, the US pledged to cut greenhouse gas emissions by between 61% and 66% below 2005 levels by 2035. This is no longer seen as binding by the Trump administration, which has already vowed to support and expand domestic fossil fuel production and to export more to the rest of the world.

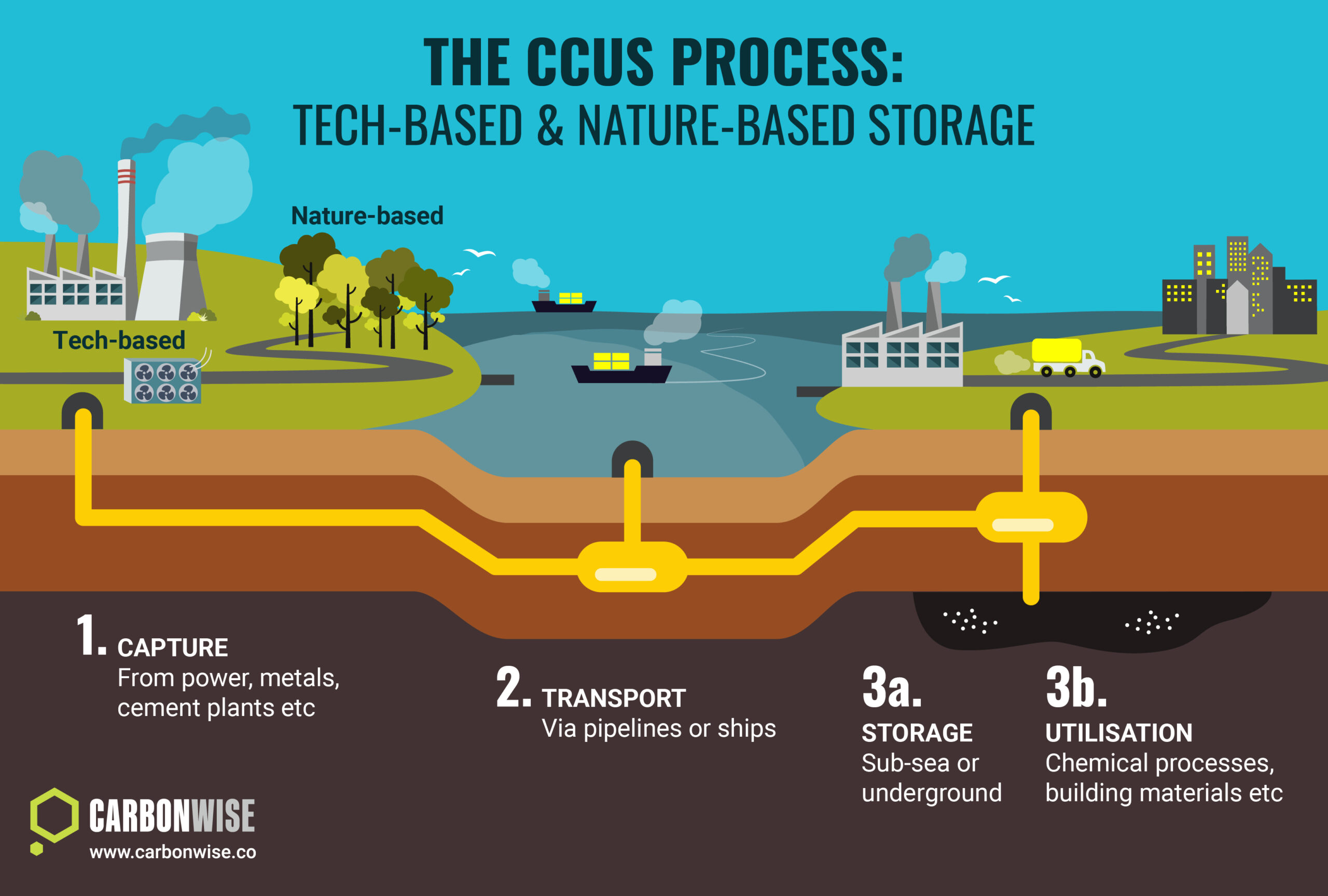

Secondly, the US will not participate in the international carbon markets under Articles 6.2 and 6.4 of the Paris treaty. This means there will be no Paris-eligible sales of US emissions reductions.

Equally, one can expect that US entities will not be able to retire Article 6 credits towards a US federal carbon target. They may well be able to continue buying and retiring such credits against their self-binding targets, but these will not be accounted for under UN rules.

This doesn’t mean that host countries from which such credits are sold would escape UN carbon accounting rules. Any sale under Article 6 must be accompanied by what’s called a “corresponding adjustment”, in which the selling (host) country adjusts its emissions target upward to compensate for reductions that it has sold abroad. The only difference would be that a US buyer would not be able to contribute to the US’ achievement of a Paris target.

And this means that US airlines who are participating in the International Civil Aviation Organisation’s CORSIA carbon market can still buy and retire authorised international carbon credits towards their own goals set by that system.

(Of course, this might change if the Trump administration were to look at withdrawing from ICAO.)

US companies active in carbon credit project development won’t be impacted by the Paris withdrawal either. They’ll be able to work in Paris-aligned countries to build projects and can even buy and sell carbon credits as usual. The Paris withdrawal only affects the US federal government.

And finally, the US compliance carbon markets in California, in Washington state and in the northeast of the US are not affected by the withdrawal. As the jurisdiction of these markets is at the state level, they too are not affected by federal actions.

Where the US withdrawal is more likely to have an impact is on the global politics of climate change. Without the US supporting the effort to achieve the Paris goals of net zero by mid-century, the chances of getting there have been significantly diminished.

And a number of other countries with climate-sceptic leadership may feel emboldened to distance themselves from previous commitments. At COP29 last year, Argentina’s populist leader Javier Milei ordered his delegation to return home, without giving any reasons.

Back in 2017 when Trump signed off on the first withdrawal, US states and corporates rebelled in great numbers. The “We Are Still In” coalition was born and was particularly active over the following three years.

But domestic politics in the US have changed; not only have a large number of financial institutions resigned from the Net-Zero Banking Alliance, but a number of large corporates have slowed or even reversed their previous climate commitments.

So far, there has been no concerted public movement like “We Are Still In” to push back against Trump’s anti-climate policies, but it may only be a matter of time.

One important element to consider is that climate ambition is being incorporated into agreements on other issues, such as trade. The EU trade agreement with the South American Mercosur bloc included pledges by all parties to implement the Paris Agreement and work towards climate neutrality. Withdrawing from Paris may be easier for the US than for most other countries, but it brings with it risks that we have yet to understand.