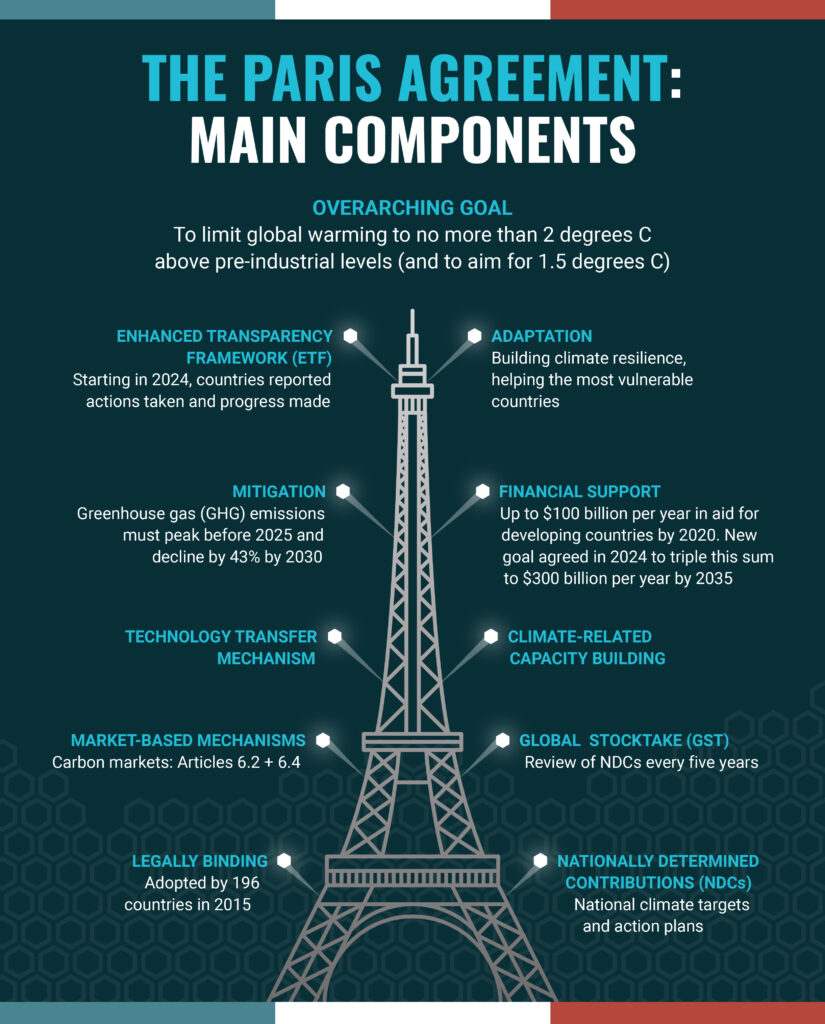

The Paris Agreement is an international treaty on climate change adopted by 196 countries in the French capital in 2015.

The agreement is a legally binding treaty agreed under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, and its overarching goal is to limit global warming to no more than two degrees Celsius, preferably 1.5 degrees C, above pre-industrial levels.

This requires massive reductions in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050 to avoid catastrophic temperature increases by 2100 that would threaten coastal cities and other low-lying areas with flooding and cause widespread droughts, crop failures, famine, critical infrastructure failure and other harm to lives and livelihoods.

Key elements

Under the Paris Agreement, countries agreed to take on voluntary emissions reduction targets and develop domestic action plans and policies to deliver them. Each country’s combined target and plan is known as its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC).

Crucially, the agreement includes a periodic review process, with governments expected to ramp up their climate ambition in five-year cycles. It also encourages transparency by promoting a peer review process among governments. The first of these “Global Stocktakes” took place in 2023.

While the process of setting emissions reduction targets itself is voluntary, once agreed, the targets become binding under the deal.

As well as GHG emissions reductions – so-called ‘mitigation’ – the agreement also encourages governments to draw up and deliver plans for adapting to the effects of climate change that cannot be avoided, such as deploying flood defences, or upgrading critical infrastructure to cope with more extreme weather events.

The Paris Agreement also includes a framework for providing technical, financial and capacity building support for countries that need it. This builds on an earlier pledge by the most industrialised countries to provide up to $100 billion per year from 2020 to help developing countries adapt to climate change and the energy transition.

A new approach

The Paris Agreement is a successor to the earlier Kyoto Protocol which countries agreed in 1997.

Under Kyoto, countries were classified into two groups: the wealthy industrialised nations were known as ‘Annex I’ countries, and the less developed nations were called ‘non-Annex I’. This latter group included the fast-developing emerging economies like China and India. Since only the Annex I countries were obliged to take on legally binding climate targets, this led some nations to reject the Kyoto Protocol on the basis that it was unfair.

As a result countries began to look for a new approach under a successor treaty that could be accepted by a larger group of nations. With this in mind, the Paris Agreement allowed all countries to submit their own emissions reduction targets, based on their capabilities, recognising different starting points and differences in levels of economic development, access to technology, energy and other natural resources.

This more flexible approach encouraged wider participation and largely ended a stalemate that had dogged the Kyoto Protocol.

Implications and challenges

The significance of the Paris Agreement is that it brought all nations for the first time into a global deal that included climate targets for all. Annual summits, called the Conference of Parties (COP) to the UNFCCC, ensure that countries regularly discuss climate ambition and progress, holding each other to account on promises made, including emissions reduction targets, policies to deliver them, and financial and technical support.

The periodic reviews and expectation of rising climate ambition under the Paris deal together send a signal to financial markets that governments will continue pursuing sustainable pathways for energy, industry, transport, buildings and agriculture. The “direction of travel” implied by the Paris deal also raises risks for new long-term investment in high-carbon fuels and industrial processes.

While the Paris Agreement was an essential milestone, it remains an insufficient response in the face of climate change. The global atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide has continued to increase every year since direct measurements began in the 1950s. And while GHG emissions are falling in Europe, the USA and other regions, emissions in China and other fast developing economies continue to increase, highlighting the difficulty in achieving the global goal of keeping climate change in check.

The Paris Agreement itself will not avert catastrophic climate change. The worst effects can only be avoided through governments, businesses and civil society continuing to find new ways to reduce GHG emissions through regulatory frameworks, new technology, consumer choices and changes in consumption patterns.