Carbon markets can broadly be broken down into two distinct types: compliance and voluntary.

Compliance markets establish an absolute limit on how much carbon dioxide can be emitted into the atmosphere by all the entities covered by the market system. This “cap” is set annually, and in order to achieve the goal of reducing emissions, it shrinks over time.

The European Union’s carbon market set an overall cap of 1.57 billion tonnes in 2021, shrinking by 1.74% a year until 2024, when the annual decrease grows to 4.3%.

Companies that emit CO2 must purchase carbon allowances to match their emissions, and surrender them each year to ensure they are complying with the market regulations.

These allowances (also known as permits) are either distributed free of charge or sold by the market regulator at regular auctions. If a company needs to buy additional allowances, or has surplus permits, these can be bought and sold in an open market.

The EU market holds auctions almost every day, while markets in California and the northeast of the US hold sales quarterly.

These sales help to generate a stable – yet steadily rising – price signal that helps companies decide whether they want to buy permits or invest to reduce their own emissions. If an emissions-reducing investment can be carried out at less than the cost of buying the permits, then it makes good economic sense to invest.

Similarly, the cost of carbon permits can help drive research into new technologies. Companies in Europe are increasingly studying how to produce hydrogen using renewable energy instead of natural gas, which could create a market for a new net zero fuel of the future. These zero-carbon technologies would not need to pay for carbon permits, meaning they can compete with legacy fuel producers.

Similarly, steel companies are studying how to minimise their greenhouse gas emissions using new processes. New ways of making steel with lower emissions would reduce their carbon permit costs.

The goal of such “cap-and-trade” markets is to ensure that emissions are reduced at the lowest overall cost to the economy. By establishing a price on carbon that rises over time, more and more new, low-carbon technologies become economical, ensuring that companies have options to transition to a net zero model.

“Cap-and-trade” markets operate in the EU, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, California, Washington state, in ten northeastern US states, New Zealand and South Korea. Dozens more countries are studying how they can introduce carbon pricing.

There are numerous variations on the “cap-and-trade” model of compliance markets. The global aviation market has established a compliance carbon credit

market, for example, which is not aimed at reducing emissions over time, but instead targets carbon neutral growth.

This aviation market, known as CORSIA, is regulated by the UN’s International Civil Aviation Organisation, and requires all countries and operators to offset any growth in emissions. Airlines must measure the greenhouse gas emissions from their flights each year, and buy and retire offsets matching any increase over their 2019 levels.

Similarly, the People’s Republic of China has developed a carbon market that currently sets a limit on the carbon intensity, that is, the volume of CO2 emitted per unit of production of its power sector. This system does not “cap” emissions in the same way as other markets – indeed, overall emissions can increase under an intensity-based system – but it does represent an interim step towards a “cap-and-trade” market.

Conversely, “voluntary” carbon markets are not regulated, since they do not have the force of law in any jurisdiction. While individual companies that serve this market may carry out business that is regulated – such as trading in derivatives contracts – the underlying carbon credits are not currently governed by law.

Instead, carbon credits are created, overseen and underwritten by independent organisations known as standards. These standards set out rules and guidelines on how carbon credits can be generated, they verify the outcome of offset projects, and issue carbon credits. The standards act as the guardians of the “quality” of the credits, such as the permanence of the reductions.

These carbon credits are then used by commercial entities or individuals to neutralise their carbon footprint (see “What is a carbon offset?”).

The decision to offset a carbon footprint is entirely voluntary. While many companies operate facilities in jurisdictions where compliance carbon markets exist, not all of their operations may be covered by such a system, and so they may choose voluntary offsetting to ensure the footprint of their entire operation is at least neutralised.

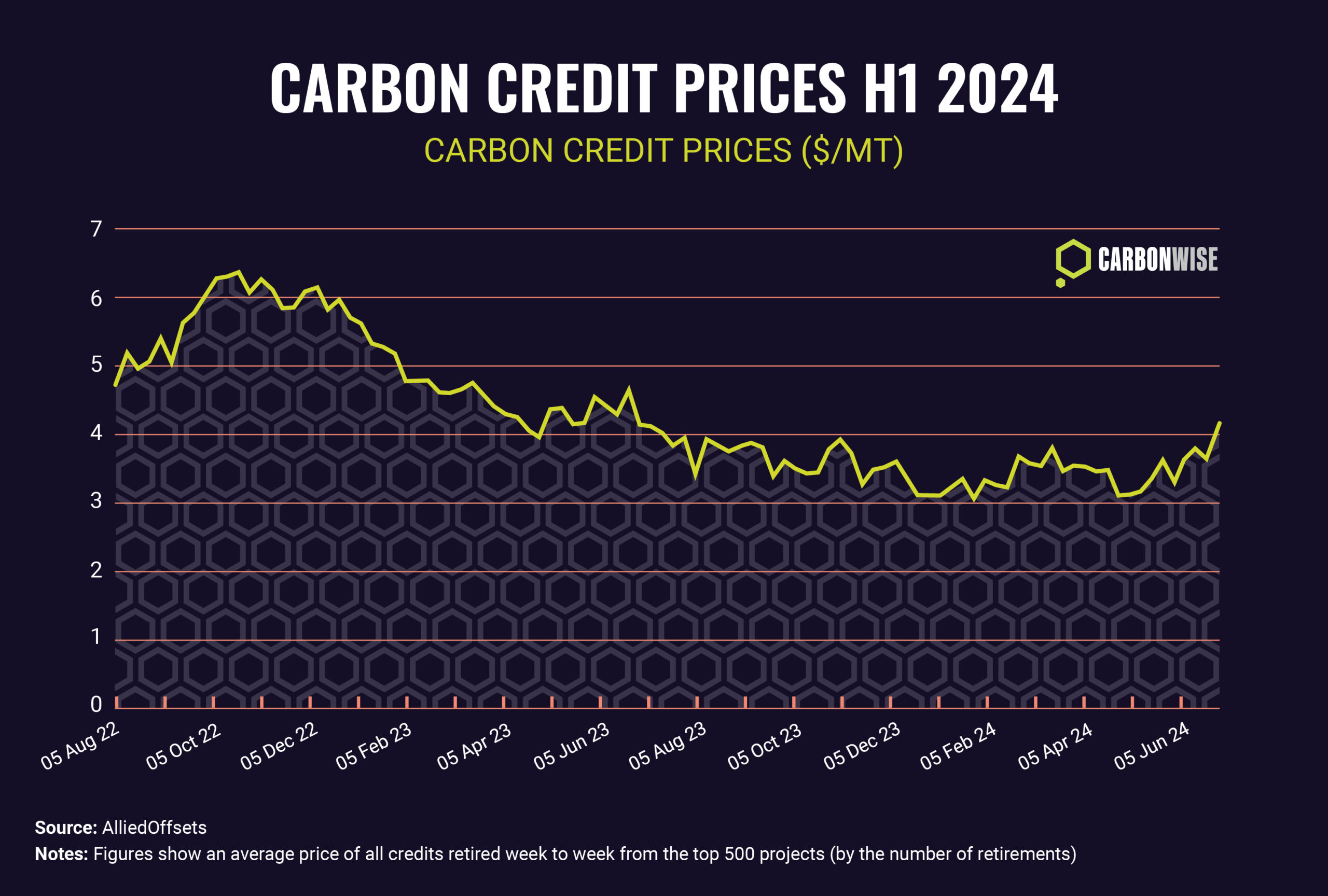

Demand for carbon credits is still considerably less than the demand for compliance permits, but this is a growing sector. As more companies take on net zero commitments, so the demand for credits will grow. Analysts

Even while no single country regulates carbon credits today, the United Nations is working to set up a global marketplace that will gather countries and businesses to participate in an official offset market. This market, currently known as the “Article 6” credit market, is expected to launch in the middle of the decade.

The UN market will not mandate the use of carbon credits, since it will be up to individual countries to choose whether to buy and retire them, but it will set thresholds for offset quality that will apply to any project that seeks to sell under Article 6.