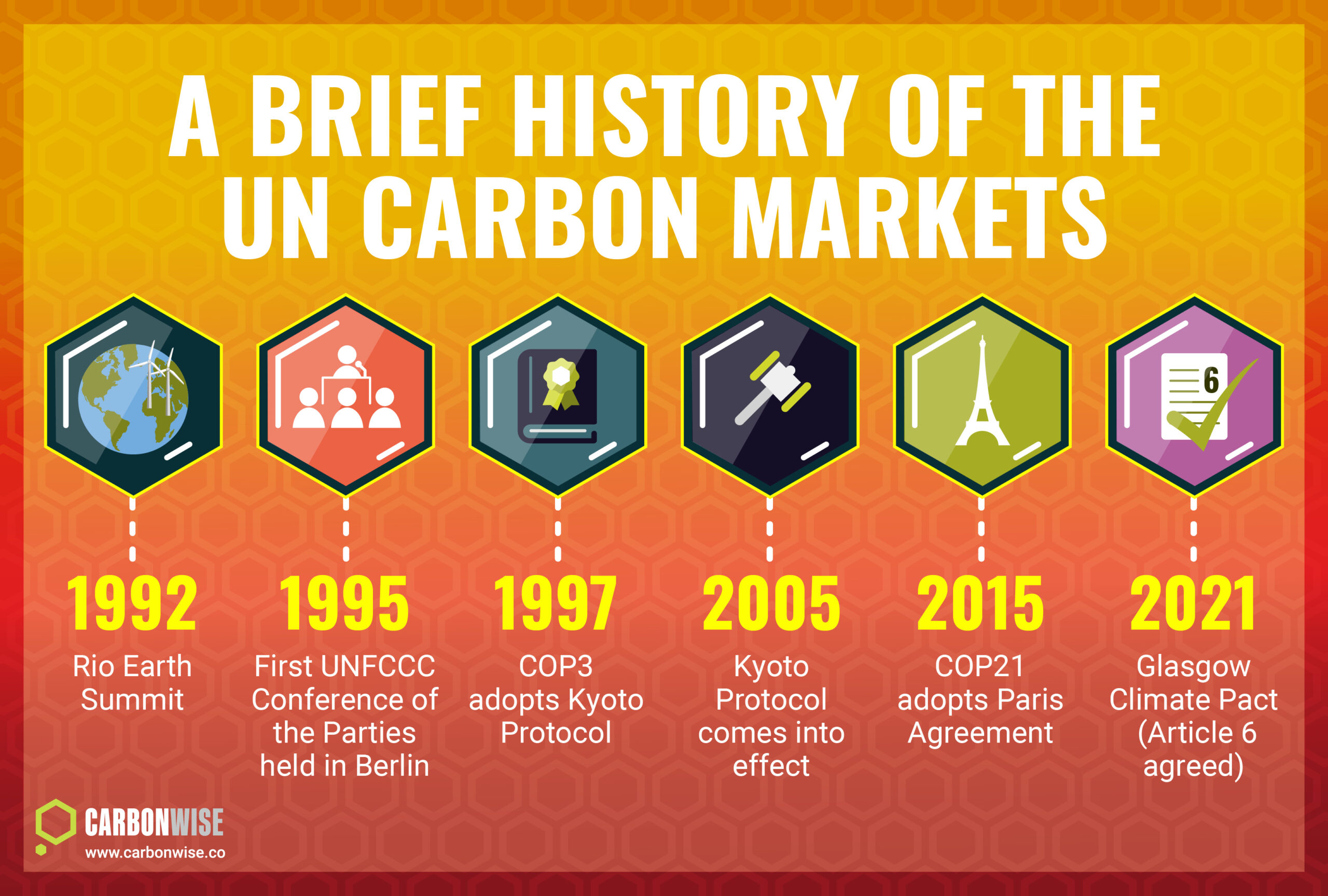

Carbon markets under the United Nations came into being during the 1997 Kyoto Protocol era, with the UN’s so-called ‘flexible mechanisms’: international emissions trading, the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and Joint Implementation (JI).

These programs were adopted under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change treaty and were designed to help provide flexibility in how countries met their national targets to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions under Kyoto.

International emissions trading centred on the idea that governments could buy and sell emissions reductions, creating a more flexible way to meet their national emissions reduction targets, and at the same time lowering the cost of achieving them. The common currency of international trading under the UN was called Assigned Amount Units (AAUs), with each unit corresponding to one tonne of CO2 equivalent GHG.

Meanwhile, the CDM allowed the industrialised countries to offset emissions by investing in emissions reduction projects in developing countries and to use the resulting credits — Certified Emission Reductions – as part of their own efforts to meet their targets.

The JI program was similar, but involved industrialised countries investing in emissions reduction projects on a bilateral basis, rather than involving developing countries.

Thousands of projects were registered, approved and monitored under CDM and JI, producing credits that were traded between companies and countries, and which led to a spot market on exchanges and in the brokered markets, as well as the emergence of trading in derivative contracts such as futures and options as the market began to grow.

Simmering tensions

However, below the surface, not all was well with the Kyoto Protocol.

Long-simmering tensions over structural elements of the accord had never completely gone away, even as the UN’s carbon markets appeared to be getting off to a good start in terms of capacity building, fostering financial transfers from rich to poor countries and enabling the deployment of sustainable technologies to less developed countries.

Underlying the apparent success of Kyoto, a rift had emerged over how the UNFCCC classified signatory countries. In simple terms, countries were dropped into one of two buckets – the industrialised countries were known as ‘Annex I’ and the developing nations were called ‘non-Annex I’.

The reason this was significant was that only Annex I countries were required to take on binding GHG emissions reduction targets under Kyoto, leaving the developing countries free to grow without climate constraints.

This classification had come about because the industrialised nations recognised that the less developed countries held less responsibility for the historic buildup of GHGs in the atmosphere; that their per capita emissions were still low; and that their share of global emissions would grow to meet their development needs.

Few objected to countries like Afghanistan, Sudan and Yemen being free of emissions reduction targets, since the poorest countries had almost zero responsibility for historic emissions and very low GDP by global standards.

However, since fast emerging economies like China and India were also classified as non-Annex I, this led to accusations of free-riding, and made it more politically difficult for some richer countries to accept binding targets, particularly ones that would become progressively tighter over time.

Industrialised countries call halt

These tensions went back to the beginning of the Kyoto Protocol.

In 1997, the year that the treaty was adopted, the US Senate passed the Byrd-Hagel Resolution, which expressed opposition to any international climate agreement that did not require developing countries to reduce emissions. This was due to stated concerns over serious harm to the US economy. The resolution passed by 95 votes to zero.

The US signed the Kyoto Protocol the following year under the Clinton Administration, but the Senate’s opposition meant the treaty was never put before the upper house, preventing America from ratifying.

Eventually other industrialised countries began to turn against Kyoto, with Canada, Japan and Russia announcing in 2011 that they would not take on further climate targets under the protocol.

The emergence of the CDM and JI was an attempt to bridge the chasm at the heart of Kyoto, by allowing the richer countries to pay for emissions reductions in developing countries – a policy that was more cost-effective than reducing emissions at home. This helped to overcome the rift over the UN’s binary grouping of countries into rich and poor, but was not enough in itself to save the protocol.

A new approach

Throughout this period, the buildup of atmospheric carbon continued year-on-year, raising the prospect of severe climate impacts unless the world changed course. At the same time, the withdrawal of several countries from Kyoto meant that demand for carbon credits from CDM and JI was much lower than expected, creating an oversupply which led to very low prices.

The political stalemate over Kyoto prompted an international re-think, and out of the ashes of Kyoto, a new approach emerged which involved voluntary commitments by all nations, not just the most developed.

This new approach culminated in the 2015 Paris Agreement, under which each country pledged to reduce emissions and develop plans and actions that would achieve the target under the so-called Nationally Determined Contributions. Furthermore, the parties to the Paris accord also agreed to commit to a five-year review mechanism that would encourage them not only to meet their existing climate targets but to raise their ambition over time.

The UN discussions since 2015 include Article 6 – the Paris Agreement’s rulebook which sets out the terms of international carbon markets. Article 6 allows countries to voluntarily cooperate with each other to achieve their climate targets, by reducing emissions and transferring the carbon credits to another country for its own use against its target.

Finding common ground on Article 6 was one of the hardest elements of the Paris Agreement to negotiate and it took until 2021 to finally find agreement at the COP26 UN climate conference in Glasgow.

The reason this agreement matters is that COP26 not only kept alive a goal to limit global warming to no more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, but also that carbon markets would play a significant role in helping countries achieve their ever-increasing commitments to reduce emissions.

Signs have since emerged that some countries may prefer to develop emissions reduction projects at home and use the reductions towards their own national targets instead of transferring them abroad. However, the carbon market mechanism still stands for those that want to use it, and the architecture that has grown up around the voluntary carbon market means that the entire system does not need to be reinvented.

How the VCM dovetails and overlaps with the emerging UN carbon markets will be a complex space to navigate, and much work is going into clarifying the rulebook, including the proper accounting for how cross-border transfers will work.