Supported by:

Cap-and-trade systems focus on large, industrial emitters, but often don’t cover emissions from smaller sources. What sort of policies exist to encourage change at individual level?

- City-level transport schemes seek to cut pollutants and GHG emissions

- Governments start to tackle emissions from smaller companies

- France targets domestic aviation emissions

- EU set to expand carbon trading to cover transport, buildings

Cap-and-trade systems to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have proliferated around the world in recent years, with varying levels of success. But outside of these systems, how are governments tackling emissions from the non-traded sectors, and in particular from smaller companies?

Cap-and-trade systems, the biggest of which is the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), have been established worldwide to cut GHG emissions and achieve Net Zero by 2050.

These are networks which set limits on the emissions that a wide range of sectors produce by offering or selling emissions allowances and encourage corporations to reduce their emissions by putting a price tag on them. The system provides companies with flexibility by allowing them to trade these allowances. This ensures that emissions reductions happen where the cost is lowest.

At the end of each year, corporations must surrender sufficient allowances to cover their annual emissions to avoid penalties. They can then retain or sell allowances based on their emission reductions. Cap-and-trade systems can monitor emissions and drive significant reductions over time effectively.

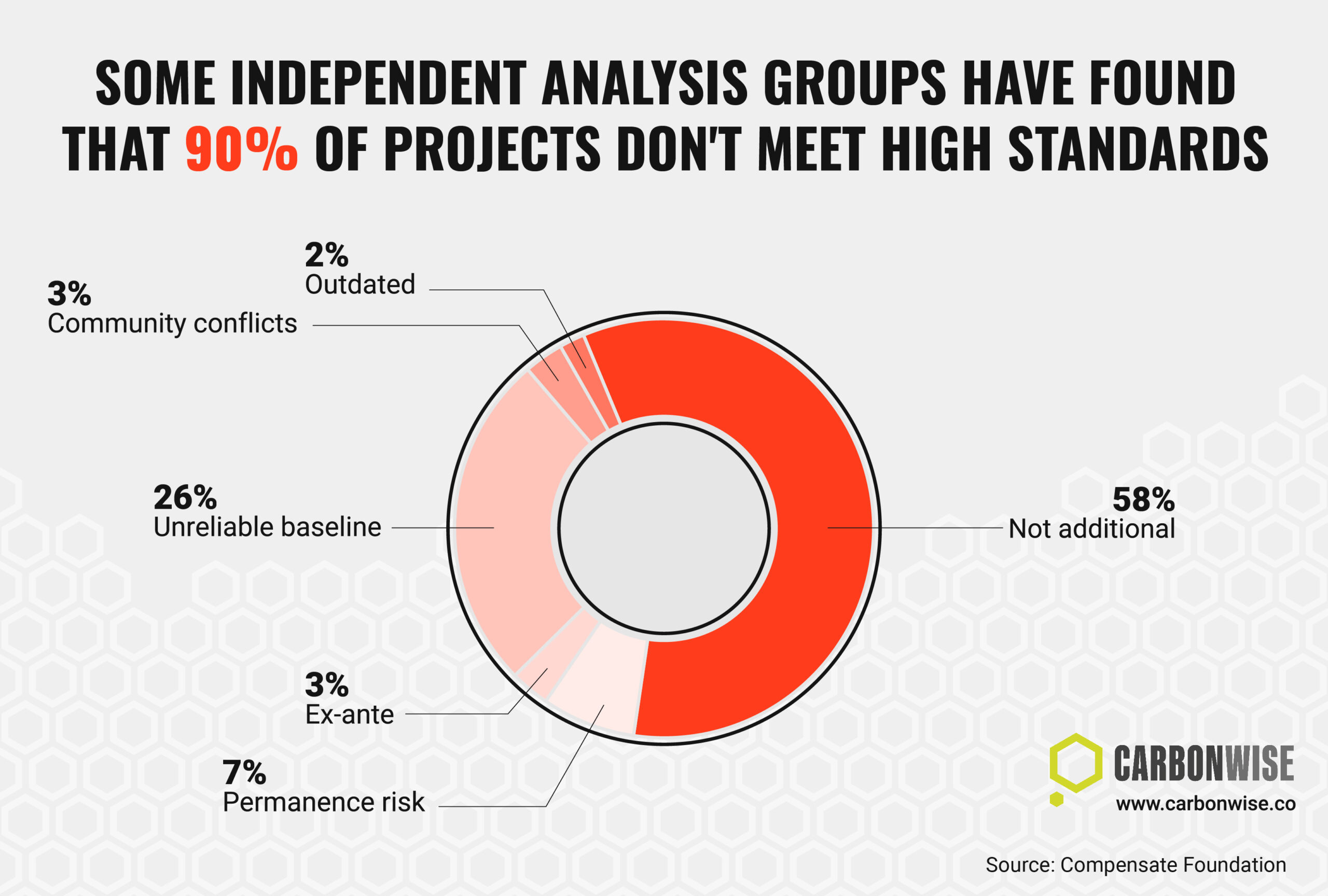

However, these systems generally cover larger CO2 emitters and thus fail to impose limits on smaller companies, whose emissions, though smaller when counted individually, are significant when considered collectively. It is harder to target smaller companies individually, and complying with a legally binding ETS represents a proportionally higher cost for smaller companies.

For example, the European Commission – the regulator of the EU ETS – states that the system is ‘mandatory for companies in the various high-emitting sectors it covers, yet ‘in some sectors, only operators above a certain size are included.’ This is because monitoring GHG emissions produced by smaller businesses is more difficult and less cost-effective.

Therefore, as well as cap-and-trade systems, nations have introduced policies to encourage change at an individual level. Nonetheless, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) view is bleak, as it highlights in its AR6 Synthesis Report: ‘Climate Change 2023’ that ‘Many countries have signalled an intention to achieve net-zero GHG or net-zero CO2 by around mid-century, but pledges differ across countries in terms of scope and specificity, and limited policies are to date in place to deliver on them.’ The implication is that the pace and number of policies introduced need to be scaled up rapidly to achieve the goal of net zero by 2050.

A notable example of an existing policy targeting individual emitters is Low Emission Zones, which can be found in major cities across Europe, including Paris, Amsterdam, Berlin and London. The Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) implemented by the Mayor of London is set to be expanded to cover all London boroughs from 29 August 2023. The ULEZ uses existing emissions standards called Euro Standards and applies them to vehicles within London, which the Transport for London (TFL) website defines as ‘a range of emissions controls that set limits for air polluting Nitrogen Oxides (NOx) and Particulate Matter (PM) from engines.’ Road transport is responsible for emitting a significant majority of these pollutants, according to the London Atmospheric Emissions Inventory (2019). The ULEZ is in place 24 hours a day, every day of the week, the only exception being Christmas Day. Drivers of vehicles that do not meet the requirements for emissions have to pay £12.50 per day to drive within the Ultra Low Emission Zone.

This provides a financial deterrent, incentivising Londoners to consider switching to greener options, such as electric vehicles. However, for this to be a viable solution for the average Londoner, TFL also indicates that ‘Londoners receiving certain low-income or disability benefits can apply to the Mayor of London’s £110 million scrappage scheme’, which would allow them to earn money in return for scrapping their vehicle, or receive a smaller amount of money as well as a TFL Annual Bus and Tram Pass, which has a greater value than the monetary payment.

London-based sole traders, micro-businesses (those with ten employees or less), and registered charities will also be eligible for the scrappage scheme or retrofitting of their vans and businesses. Moreover, as of the end of July 2023, this will extend to cover a greater number of businesses and charities.

While London’s ULEZ scheme targets specific air pollutants that are harmful to human health at the local level rather than GHGs, the system nevertheless can play a role in cutting GHG emissions as drivers begin to scrap their older internal combustion engine vehicles in favour of those with more efficient engines, or lower emissions models such as electric vehicles.

However, in many other respects, the UK’s climate policy is falling behind, as Fiona Harvey outlined in an article published in the Guardian in June 2023, which discusses the independent cross-party Climate Change Committee’s report on climate policy progress. ‘Fewer homes were insulated last year under the government-backed scheme than the year before, despite soaring energy bills and a cost of living crisis. There is little progress on transport emissions, no coherent programme for behaviour change, and still no decision on hydrogen for home heating.’ The Climate Change Committee’s report also emphasised that the current pace of developing wind and solar farms in the UK and reforming the electricity grid is too slow to reach the goal of net-zero by 2050. This raises concerns about the progress that must be made to avoid a further increase in global temperatures.

On the other hand, in France, a recent policy has been introduced at a national level to reduce carbon emissions produced by air travel. The French government has banned all domestic flights which can be replaced by a rail journey that takes less than two and a half hours. As an article published by the BBC reveals, ‘The ban all but rules out air travel between Paris and cities including Nantes, Lyon and Bordeaux, while connecting flights are unaffected.’ This is a significant move in environmental policy, since it is the first European country to have imposed such a prohibition. Even so, it has been criticised for being a “symbolic ban”, since domestic air travel accounts for few emissions compared to international flights. Nevertheless, this policy remains a step in the right direction since air travel contributes much more to an individual’s carbon footprint than if the same journey was made by train. It also suggests the possibility for further policies to be introduced to reduce emissions.

The European Union is also making changes to its climate policy, as it is introducing EU ETS II, ‘a separate emissions trading system for fuel combustion in buildings, road transport and additional sectors (mainly small industry not covered by the existing ETS,’ according to the European Commission. This new ETS will be set in motion in 2027, although the EU intends to commence recording and tracking the emissions produced by the sectors it will cover in 2025. The cap that will be imposed upon these sectors will lower emissions by 42% by 2030, and through this, the EU hopes to meet its goal to cut economy-wide GHG emissions by at least 55% below 1990 levels by 2030.

The EU Commission has also established a Social Climate Fund, which will provide a buffer against the effect that the new ETS will inevitably have on poorer social groups. This will be launched in 2026, and the European Commission stipulates that it ‘can be [used] in energy efficiency and the renovation of buildings, clean heating and cooling, and integration of renewable energy as well as in zero- and low-emission mobility and transport, including public transport.’ The money for the fund will be raised by contributing some of the revenue from auctioning emissions allowances. The remaining revenue will be given to EU Member States, and will ‘have to be spent for climate and social purposes.’

This is a significant change in the EU’s environmental policy, since it seeks to resolve the aforementioned issues with the original EU ETS, notably that it does not cover smaller sectors whose collective emissions are considerable. It will also have a greater impact on diminishing the individual’s carbon footprint since it will place firm limits on the emissions produced by housing and transport. EU nations will have to ensure that the vulnerable are protected from increasing costs during this time, including rising energy bills, and the Social Climate Fund is meant to provide support in this respect.

Ultimately, cap-and-trade is considered an effective way to reduce carbon emissions since it incentivises businesses to find ways to become more environmentally friendly in a cost-effective manner, allowing them to trade any allowances they do not need. The development of the EU ETS shows that it can be expanded and improved upon to cover a wider range of sectors and provide assistance to those affected the most by these changes. Other options include restrictions on transport through Low Emission Zones, which can be found all over Europe, and blanket bans on certain types of travel, such as domestic flights. The measures that are being introduced remain a promising start, but there is more that needs to be done, and quickly, if collective climate goals are to be met.